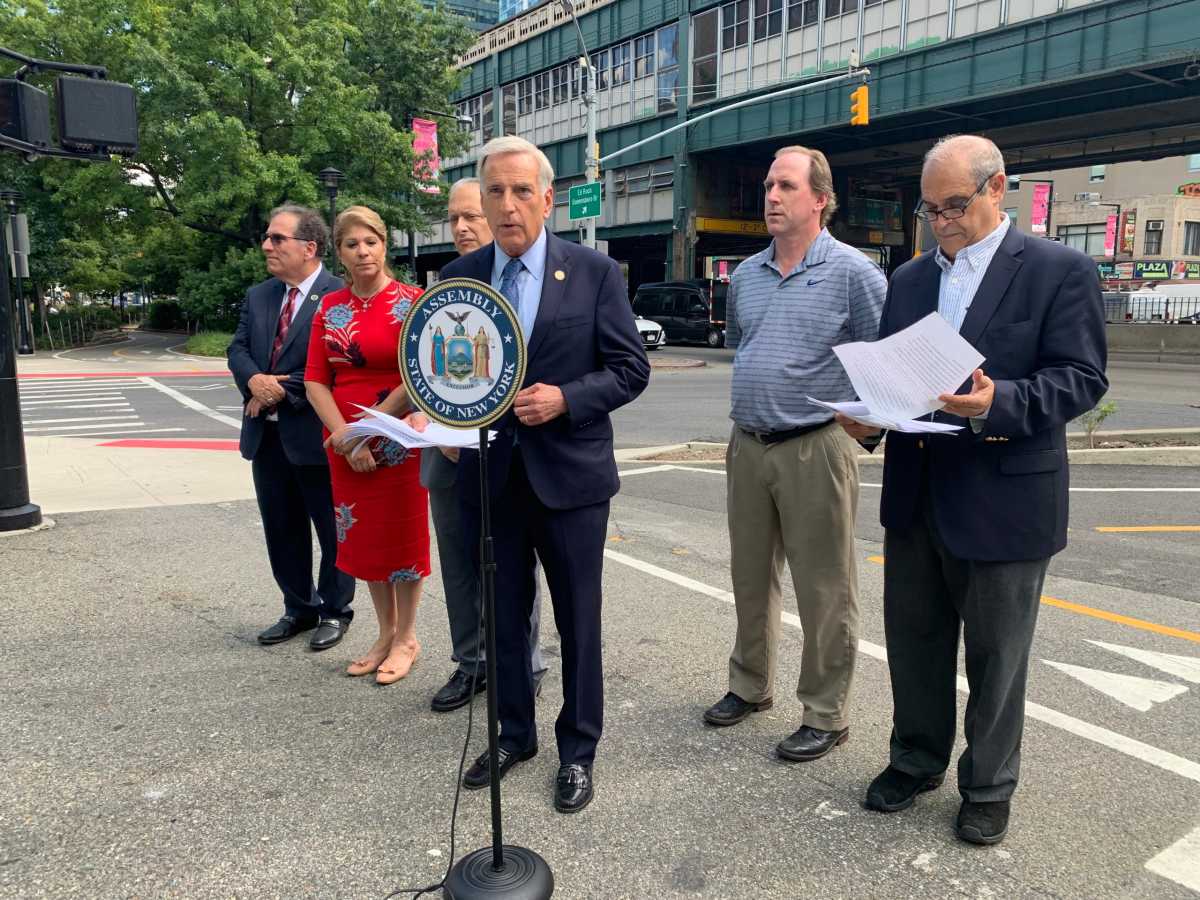

At the foot of the Queensborough Bridge Wednesday, Assembly Member David Weprin (D-Queens) said he’d introduce a bill to push back the implementation of the MTA’s forthcoming congestion pricing plan from early 2024 until at least December 31st 2028 in the upcoming state legislative session.

The congestion plan will impose a surcharge on motorists entering Manhattan’s Central Business District (CBD) below 61st Street to raise sorely needed funds for the financially strapped transit agency. Weprin, although not totally against the plan, is highly skeptical and thinks at the very least it must be delayed considering the city is still reeling economically from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Congestion pricing is not, and I say not, a fair deal for New Yorkers,” Weprin told reporters. “It’s another outer-borough tax that will cripple families and businesses across New York City at a time of rapid inflation, while we are still recovering from the COVID-19.”

Weprin said those living in his eastern Queens district will be adversely affected by the program because many of them rely on driving to get to Manhattan, due to the fact that the far flung section of the World’s Borough has limited public transportation options.

“My district, which largely straddles the Grand Central Parkway, is a public transit desert and will be one of the most adversely impacted by the imposition of the proposed congestion pricing tax,” Weprin said. “A trip into Manhattan can often take two hours, and often requires hopping on two buses and two Subway lines. Whereas driving more than cuts that time in half. Many of my constituents have no viable transportation options other than driving.”

Weprin was joined by others opposed to the plan including The Black Car Fund Executive Director Ira Goldstein, Long Island Farm Bureau Administrative Director Rob Carpenter and Arthur Miller, an attorney and publisher of the trucking industry blog New York Truck Stop.

The polarizing congestion pricing issue was thrust back into the news cycle earlier this month when the MTA released its possible tolls and exemptions for the plan as part of a federally-required environmental assessment, as reported by amNewYork Metro. Tolls on drivers entering the CBD could range between $9–$23.

The MTA expects to raise $15 billion from the plan, bringing in $1 billion in tolls a year, with the goal of funding a large chunk of its current five-year capital plan to improve the region’s aging public transit system. The toll is also aimed at cutting congestion in the CBD – by one fifth of its current levels, the MTA expects – and reduce air pollution by pushing more people to utilize the subways and buses.

Proponents of congestion pricing see the plan as critical for funding capital projects to improve the decaying transit network, including its aging signal system and making more stations wheelchair accessible.

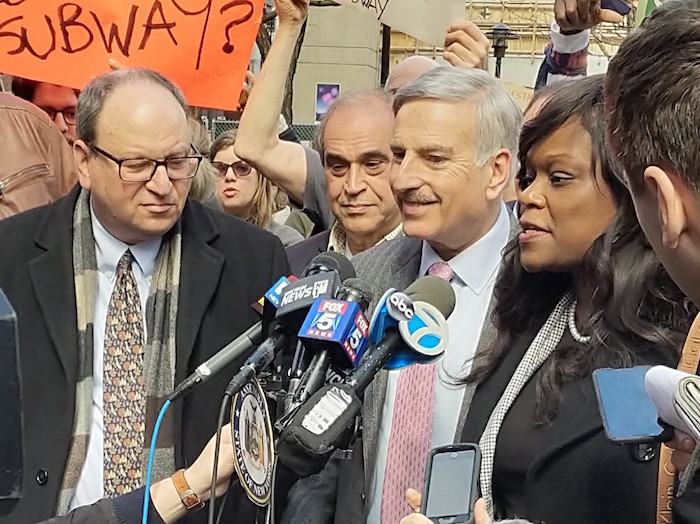

“Don’t just let the nays be the ones that are heard. This will give us cleaner air, clearer streets, faster buses, a much more resilient transportation system,” said Andrew Albert of the New York City Transit Riders Council, the MTA’s in-house commuter advocacy group, at a rally outside Grand Central Terminal last week.

Weprin is hardly the only person with a strong opinion on congestion pricing. Several hundred people, including Weprin himself, signed up to testify at six online sessions the MTA held over the past week to gather the public’s feedback on the plan.

Many politicos from the outer-boroughs and city suburbs, as well as those representing taxi and app-based drivers, have called for various kinds of exemptions from the toll. But the more carve-outs that get tacked on, the higher the toll’s price for those who do have to pay it will be.

Weprin said the MTA is “notorious for mismanaging funds” and there should be a focus on reforming the agency before congestion pricing is allowed to move forward.

“What happened to their $15 billion in federal funding that came from Washington at the height of the pandemic?” Weprin asked. “Where is that money? I hate to tell you, it’s pretty much exhausted by the MTA’s mismanagement. The MTA is unaccountable, untrustworthy stewards of public funds. We must focus on fixing the MTA and making it accountable before we impose this unnecessary tax on working drivers from the outer-boroughs among others.”

The lawmaker, however, offered no specific ways to address the agency’s mismanagement when asked by PoliticsNY.

In response to Weprin’s announcement, the MTA sent an emailed statement to PoliticsNY listing improvements it’s made to Queen’s public transit in recent years. MTA spokesperson Aaron Donovan, however, didn’t address Weprin’s proposal to postpone congestion pricing’s implementation or his accusations that the agency is mismanaged.

“Nearly 90% of Queens residents – people of all incomes – rely on a well-funded, functional transit system to reach the Manhattan central business district,” Donovan said. “The MTA has improved service in Queens by modernizing subway signals on the borough’s busiest lines, making buses faster and more reliable by redesigning the borough’s bus network, adding 40% more LIRR trains and adding a new terminal in Manhattan, and offering discounted LIRR travel to Queens residents via enhanced CityTicket program, a 10% reduction on monthly passes. The MTA welcomes all comments on the environmental assessment as part of the federal review process.”