It’s a battle between transit-starved Eastern and transit-rich Western Queens when it comes to the state legislative battle over congestion pricing – the plan to charge motorists a fee for driving into Manhattan below 61st Street.

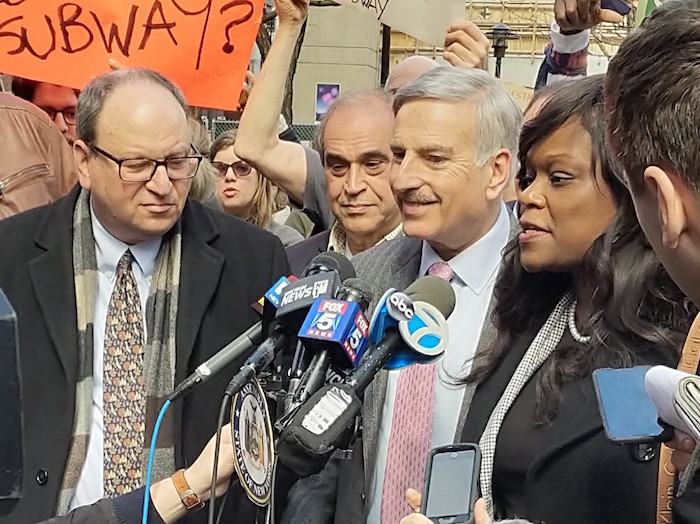

“New York’s struggling middle class cannot afford another regressive tax in the form of congestion pricing,” said Assemblyman David Weprin (D-Fresh Meadows) at an anti-congestion pricing press conference Sunday at the base of the Queensborough Bridge at Tramway Plaza with several other Eastern Queens lawmakers.

“This debate should not be rushed and we need to look to alternatives that penalize congestion and tax the wealthiest New Yorkers,” he added.

A recent Quinnipiac poll indicated that some New Yorkers feel that they can’t afford to stay in the Empire State and may consider relocating altogether, according to Weprin’s office.

According to the Quinnipiac poll, 35 percent of poll-takers said they “will be forced to move in the next five years for better economic opportunity.”

Weprin said the only way he will support congestion pricing is if the five boroughs were exempt from the toll.

“They are talking about various exemptions, and I said ‘if you exempt New York City residents from all five boroughs I will support it,’ but that does not look like that is necessarily on the table,” said Weprin. “This does nothing to reduce congestion, this is just a tax with driving into Manhattan.”

If the state really wanted to reduce congestion, Weprin believes there should be stipulations in dealing with getting liveries off highways, double-parked trucks off roads, people getting reduced fines for double-parking and having too many Uber and Lyft vehicles on the road.

“Ironically, Uber and Lyft support this because they are worried about getting taxed themselves,” said Weprin. “They are the ones causing the congestion. If you go to midtown Manhattan almost every vehicle has a TLC plaque, but they are not green or yellow. They are black or grey and just people driving their own car.”

Weprin represents Glen Oaks, Richmond Hill, Jamaica Hills, Briarwood, Holliswood and South Richmond Hill, and said that some of his constituents have to take two buses to the subway and may not make it in time to the city for work or an appointment.

“It takes them an hour to get into the city by car,” said Weprin. “We don’t know what the charge is going to be. There is no detail of who is going to be in charge of lowering it or raising it. The TBTA, a subsidiary of the MTA, will basically decide the congestion tax. So I don’t like it.”

The assemblyman believes this will also hurt small businesses that have to drive their product into the city.

“They say you only have to pay the congestion tax once, even if you have to go into the city multiple times, but I haven’t seen that in writing,” said Weprin. “It will have a negative effect on small businesses and it’s a quality of life issue for New York City residents. They are being nickel-and-dimed to death.”

Councilman Barry Grodenchik (D-Oakland Gardens) believes that people from Queens will be hit the hardest if congestion pricing gets approved unchecked.

“Many parts of the city lack accessible and efficient transportation options and the residents of Eastern Queens would be hit hardest by congestion pricing’s financial burden,” said Grodenchik. “We cannot tax our way out of a transit crisis, and writing the MTA a blank check neither addresses the agency’s longstanding underlying challenges nor sets up a sustainable solution.”

But Assemblywoman Catalina Cruz (D-Jackson Heights), a representative in northwest Queens of Jackson Heights, Corona and Elmhurst, said she is ready to vote for congestion pricing. The 7, E, F, M and R trains pass through her district along with several buses.

“Particularly in my district, I have a transit hub that is very problematic,” said Cruz. “I have 74th Street and Roosevelt Avenue and there are several train lines and buses that come out of that one place, and if one breaks down, the other breaks down then the other one breaks down.”

Her constituents are highly dependent on the subway and buses to get into the city, but both forms of transit do not run on time and she wants repair times for both to stay on their proposed timelines.

“After looking at what congestion pricing could do to help, it could help to alleviate the transit problems in my district in particular,” said Cruz. “I believe it is the right way to go to get the money that is needed and a large number of my constituents seem to agree to that.”

Cruz believes that many in the New York Assembly support congestion pricing, but are cautiously optimistic and hope that more will be fleshed out for the measure.

“I think that we will get a little more resolution here and that we will get more clarity and preciseness into who has oversight into the money and how the money will be spent,” said Cruz. “Those of us are supportive of the plan hope we will get something more precise once the dust settles and that we will have an actual proposal passed.”

Cruz wants the entire transit system to be examined, the rate of repair time for trains and buses to be faster, and for both modes of transportation to come on time.

“I see some support, but cautious support,” said Cruz. “Unless something strategic drastically happens that doesn’t look like what we need it to look like – I’m not seeing how I would not vote in support of it.”

Congestion pricing is one of the line items that state Legislators must vote for or against on March 31 in order for New York’s $175 billion 2019/2020 state budget to be finalized on April 1, according to Weprin.

According to assembly sources, it does look like some kind of congestion pricing deal will be reached with a number of yet-to-be-disclosed carveouts