A woman in blue surgical gloves and a black face mask sat on one side of the table. Ballots in hand, she slowly flipped through them one by one stacking them neatly in front of her.

“Pesach, Pesach, Pesach…” she said over and over again, repeating the candidate’s name as if guided by a metronome.

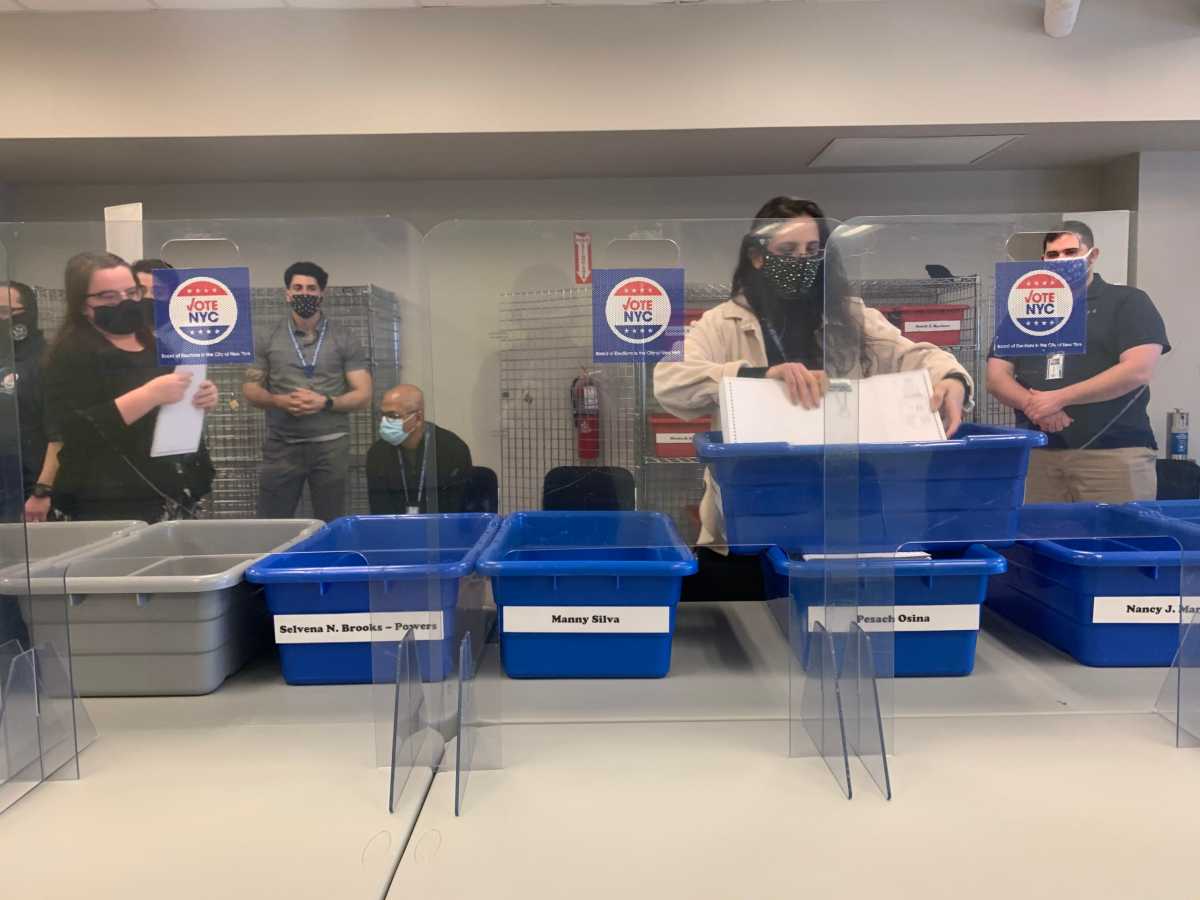

Every time she spoke and put down a ballot, the man seated to her left picked up his red pen and ticked a mark next to the candidates name on the sheet of paper in front of him. Across the table representatives from the various campaigns, including candidate Pesach Osina himself, observed the count. They sat there, separated by a glass barrier erected to help prevent the spread of COVID-19, their eyes trained on the growing piles of ballots. When those piles are complete, they will determine which candidates are one step closer to victory.

It was noon on Tuesday and the New York City Board of Elections was only part way through the first round of ballot canvassing in the first ranked choice voting (RCV) ballot count in the city’s history. The special election, which took place on February 23, was to fill the city council seat for District 31 which encompasses Arverne, Brookville, Edgemere, Far Rockaway, Laurelton, Rosedale, Springfield Gardens in Queens. The office was vacated in December by former seat-holder Donovan Richards when he took the office of Queens Borough President.

Nine candidates ran to serve out the rest of Richards’ term –– Nancy J. Martinez, Selvena N. Brooks-Powers, LaToya R. Benjamin, Latanya Collins, Sherwyn A. James, Nicole S. Lee, Pesach Osina, Shawn Rux, and Manuel Silva.

Although it isn’t the first election to use RCV, it is the first to put the new voting system fully to the test. According to preliminary results, no candidate took the more than 50% of the vote needed to win on election night. Instead, Brooks-Powers was in the lead with approximately 38% of the vote followed by Osina in a close second with 35%, triggering a RCV count.

The count, which is taking place in a desolate New York City Board of Elections office in Middle Village, Queens squirreled away in the Metro Mall on Metropolitan Avenue with a Raymour and Flannigan, a Fitnation gym, and the New York City Department of Corrections’ Training Academy, is precursor for what’s to come in June when voters head to the polls to cast their ballot in multiple citywide, boroughwide and city council primaries.

All of those elections will be using RCV, a newly implemented method of voting in the city that requires voters to rank their top five candidates in order of preference on their ballots instead of picking just one. If no candidate takes more than 50% of the first choice ballot picks, the count goes on. The candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and the voters second choice is distributed.

It’s a more complicated method of voting which, without a properly trained public and board of elections staff, can be rife with error.

The ballots the BOE employee was counting were filled out every which way. Some were completed properly, with five candidates ranked in order of preference. Others had one candidate ranked for all five spots, a line of filled in bubbles going across the page next to the name. Some only had one bubble filled in with the voter opting to not rank candidates at all.

One voter’s ballot in particular sparked a conversation between the election officials and the campaign observers.

The voter had left their top choice blank creating a middling crisis: Would their ballot count?

“So that one will count as a first choice?” a representative from a campaign said about the voters second choice vote.

“Yes,” a woman from the BOE responded.

And so history and a precedent were made.

Every once in a while a ballot came up that was what they call “overvoted” –– the voter filled in multiple candidates for the same ranking. Those ballots were classified as “exhausted” and essentially thrown away.

Michael Lambert, a political consultant working with Osina’s campaign who was watching the canvass said that it was good to see the process play out in person because it’s exposing flaws in the way the system is being implemented before multiple RCV counts happen in June at the same time. For example, a voter is supposed to be notified when they submit their ballot to the scanner that they overvoted so they can correct it. Apparently those overvoted ballots slipped through the cracks, he said.

But they didn’t slip through the cracks. When confronted with an overvoted ballot on election day, the voter has the option to “cure” the ballot or submit it as is, said Valerie Vazquez, a representative for the BOE.

Standing just feet away from the table with the ballots, Lambert gestured at the nearly two dozen BOE employees hard at work.

The RCV count is time and labor intensive, he said. Just imagine, he added, what this is going to look like in June when they have to hand count every ballot in a race that isn’t determined on election night.

But then he remembered the complications with the overvoted ballots.

“Hand counting may not be the worst thing,” he said.

Fifty minutes had passed and it was nearly lunch. It was time to stop. Everyone needed to eat. The workers behind the glasses moved quickly, putting the uncounted ballots back in their proper boxes and locked them away in metal cages at the back of the room. The counted ballots were locked away too. The tables cleared, only remnants of the mornings work remained –– a crumpled up yellow Post-It notes, orange rubber bands, red pens and binder clips were scattered across the tables. Rubber finger tips used to protect the counters fingers lay discarded near their work stations. They would be picked up soon enough.

The count was only a quarter of the way through the first round. There were more to go. There was still a lot left to do.