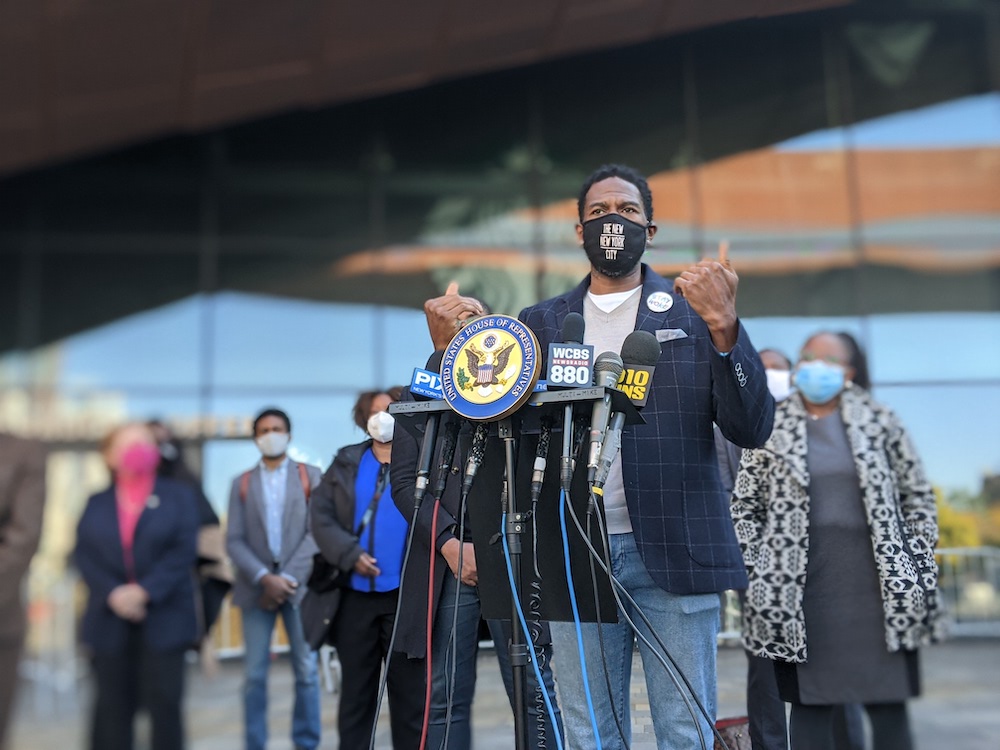

Public Advocate Jumaane Williams and Department of City Planning (DCP), along with New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), seem split on the impact of the city’s rezonings to neighborhood displacement.

This past Monday, January 11, Williams continued pushing for a racial impact study bill, 1572A, that necessitates an impact report for certain land use applications to be passed. In the city council hearing for the legislation, Williams called out DCP and HPD for “punting” the bill and disagreed with the city agencies that there was no specific causality between rezonings and displaced residents.

“It’s very long overdue,” said Williams. “The way in which land is rezoned in our city has subsequently made it difficult for many New Yorkers to find a home, let alone stay in their homes.”

The bill, first introduced by Williams in 2019, would require a racial disparity report in the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process that includes “an analysis of demographic, social, economic, and housing conditions and trends as well as identification of potential measures that may address any identified disparities or displacement risk.”

Williams said ULURP and the Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) programs are problematic as they currently are and have led to massive gentrification, exclusion, and displacement.

Specifically, said Williams, the Park Slope 4th Avenue rezoning in 2003 and the Greenpoint rezoning in 2005. The 2019 study by Churches United For Fair Housing (CUFFH) found that Park Slope lost about 5,000 Black and Latino residents in between 2000 and 2013, and found a significant decrease of about 15,000 Latino residents in Greenpoint and Williamsburg between 2000 and 2015, despite the overall population growth in both neighborhoods.

Williams said these are prime examples that communities need to have input, transparency, and a racial impact study done before any rezonings are approved. “That ‘we don’t want development.’ Nothing could be further from the truth, we just want to make sure it’s developed in a way that doesn’t leave anyone behind,” said Williams.

Councilmember Rafael Salamanca Jr. (D-Bronx), who chairs the Committee on Land Use, also chimed in with some supporting facts and figures about the general social and economic status of the city. Salamanca said that the income of median white households in the city was more than double that of Black and Latino households and discriminatory land use practices before the severe impacts of the COVID-19 crisis only worsened that disparity.

He also noted that the life expectancy across the Bronx and Central Brooklyn is years lower than across lower-Manhattan and Queens.

“The analysis proposed by the bill would identify trends, social and economic indicators, and disparities in data for a project,” said Salamanca. “It will not solve New York’s racial crisis on its own but this bill can help begin institutionalize the goal of racial equity in our land use decisions.”

DCP Executive Director Anita Laremont said she agreed that the bill was an important discussion and insisted that DCP is wholly committed to advancing fair housing in the city and ending the legacy of discrimination and ongoing inequities. Both Laremont and HPD’s Assistant Commissioner Lucy Joffe referenced the Where We Live NYC housing plan as aligning with many of the goals in the racial impact study bill.

Laremont said that concerns about displacement and disparate outcomes shouldn’t just be limited to rezonings and upzonings considering only 1 to 2 percent of the city has been rezoned since 2014.

“The greatest disparities exist across and between neighborhoods rather than within them, and the lack of housing for all people who need it is a root cause of displacement pressure in neighborhoods throughout the city,” said Laremont in the hearing. “While we acknowledge the very tangible concerns about displacement, we also caution against attributing a causality between rezoning, construction, and demographic change. Or suggesting that future demographic patterns can be predicted with or without zoning changes.”

When asked to clarify by Salamanca and Williams, she elaborated that they may have a difference in opinion about what causes displacement since it’s happening all the in the city and due in large part to “economic forces.” She said they can’t ascribe the cause of these changes to rezonings specifically, and that rezonings do provide opportunities for affordable housing.

Williams said that he was disappointed in these responses from the city as to what the housing challenge is and how the disconnect causes gentrification in Black and Latino communities. “I think your framework at the beginning is just wrong,” said Williams. “To try to pretend that the rezoning in a city doesn’t have an impact is just wild to me.”

Laremont said that DCP does in fact support working on the bill and agrees that they need more data on racial demographics and the issues raised in the hearing. “We’re not punting and saying we have Where We Live so we don’t need to talk to you,” said Laremont.

The council is set to vote on the bill this January 27.