Democracy doesn’t work if you don’t know how to vote. And the next time you step into the voting booth, the way you cast your ballot may be unfamiliar to you.

Beginning this year, New York City will implement ranked choice voting (RCV) in primary and special elections for local offices. The first two elections to use the new way of voting will be the February special elections in Queens. On February 2, City Council District 24 will vote to replace former City Councilmember Rory Lancman and on February 23, City Council District 31will vote to replace now Queens Borough President Donovan Richards.

So, what is RCV and why has it spawned so much controversy since being adopted last year?

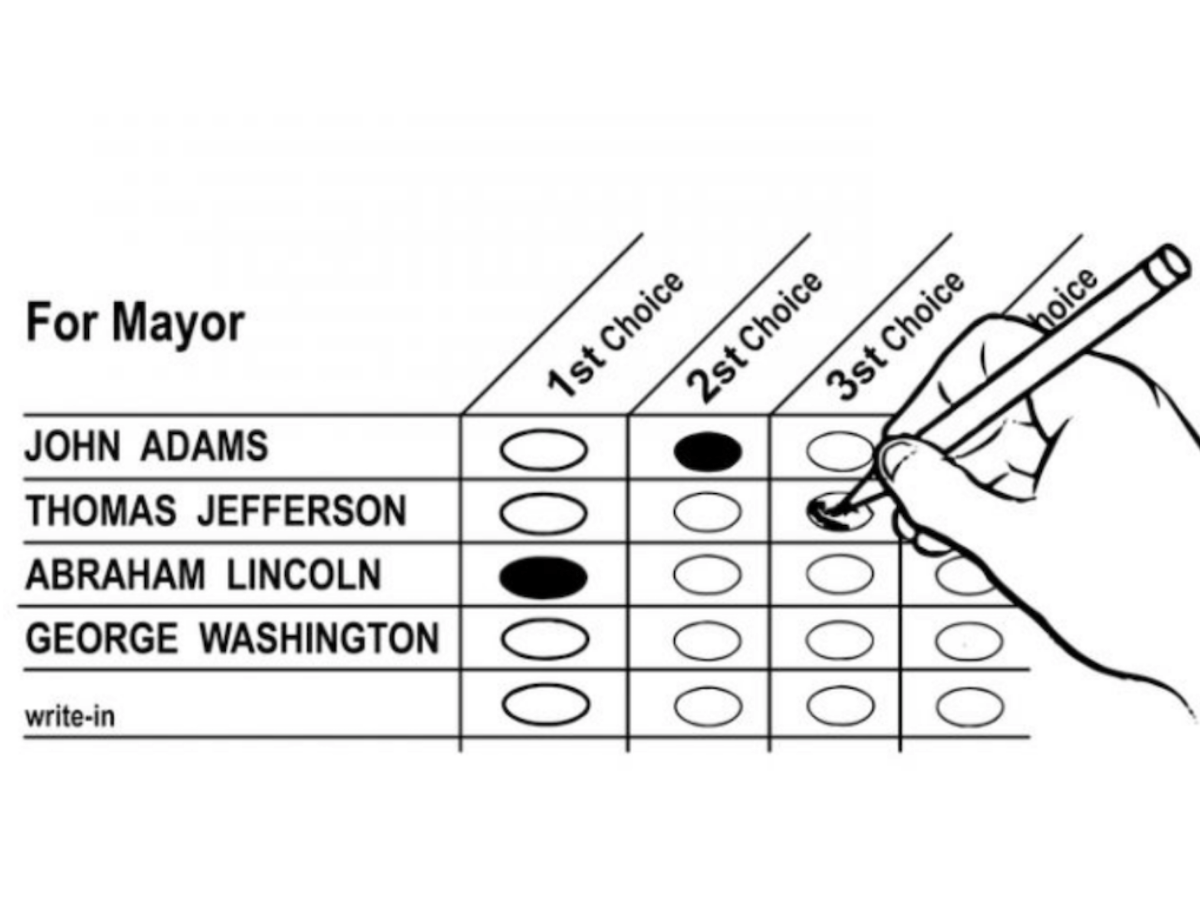

Under the new system, voters rank up to five candidates in order of preference rather than casting a ballot for just one. This ballot looks similar to the traditional one –– a scantron with multiple ovals for you to fill –– but instead of filling in a bubble for just one candidate (your favorite), you fill in a bubble for all of them. If you are voting in a five candidate race, you would mark your first choice in position one, your second in two, and so on until you reach your last choice which goes in position five.

The first choice votes are then tallied and if no candidate gets the majority of the vote –– 50% plus one –– the candidate who received the least votes gets eliminated and their second choice votes are parceled out to the remaining candidates. This process continues until one candidate has attained a majority and wins.

As of November 2020, Maine is the only state to have implemented RCV at the federal level. Several others adopted the voting system on the state level but have yet to put it to use. New York will be the most populous city so far to implement RCV, tripling the number of voters using it nationwide.

But since being approved last November, RCV has received mixed responses. Proponents tout the fact that a higher proportion of RCV voters will have at least partially backed the winner, having placed them in second or third on their ballots. This is compared to in traditional voting where a polarizing candidate who might be despised by a majority of the electorate could win, an outcome virtually impossible with RCV. Even if the majority of voters are divided among two other candidates, by placing the polarizing candidate in last place, the majority will have eliminated them from the race.

Supporters also believe the system will discourage negative campaigning, prompting candidates to reach out to more voters who might place them in second instead of relying on a narrow base. In addition, they believe voters will be more compelled to choose their true favorite without worrying about wasting a vote on someone who can’t win. Voters will also have more incentive to educate themselves on every candidate, as each one will need to be placed. In this way, the new process might not only lead to more amicable campaign practices, but might also encourage candidates to form partnerships with one another, running as a first-and-second-choice team, supporters say.

Another benefit of RVC, also known as “instant-runoff voting,” is that they avoid the costs of run-off elections in the case of an unclear outcome. With RCV, the runoffs happen instantly, with use of an algorithm so the costs normally associated with runoff elections are effectively eliminated.

Yet, despite these claims to fair voting, shrunken costs, and camaraderie on the campaign trail, RCV has amassed its fair share of opposition, in part due to the restrictions of the ongoing pandemic. In December, six New York City councilmembers filed suit in State Supreme Court, seeking to halt the implementation of the city’s new voting system. The city’s Board of Elections (BOE) won’t be able to educate voters in time, the councilmembers said.

“We have no confidence in [the Board of Elections’] ability to acclimate voters to a system of Ranked-Choice Voting’s scale and complexity, particularly within a compressed timeframe already constrained by the pandemic, given its abysmal record of performance,” wrote City Councilmembers I. Daneek Miller (D-Cambria Heights, Hollis, Jamaica, St. Albans, Queens Village, and Springfield Gardens) and Adrienne Adams (D-Jamaica, Richmond Hill, Rochdale Village, South Ozone Park), who lead the Council’s Black, Latino and Asian Caucus, in a letter to Council Speaker Corey Johnson (D-Manhattan).

The lawsuit was filed against the city, the BOE and the Campaign Finance Board (CFB), contending that the city and the two boards were violating the law by failing to conduct sufficient public education and familiarize voters with the new system. In mid-December, however, a state judge denied the temporary restraining order to upend RCV, although the initial ruling has since been appealed. The councilmembers are seeking to prohibit the implementation of RCV for use in the upcoming special elections, including two in Queens in February, which are poised to be a trial run for the June citywide primary elections.

One leading Black mayoral candidate, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, said he agreed that the system is being rushed.

“Everyone knows that every layer you put in place in the process, you lose Black and brown voters and participation,” said Adams in November.

Although he was an original backer of RCV when it was voted on in 2019, Adams has since revoked his support, contending that the BOE is failing to properly educate voters about the program.

However, Bertha Lewis, president of the Black Institute, said it was insulting to think that Black voters wouldn’t be able to understand or educate themselves on the new system.

“Let me say it plainly: Black voters are not stupid,” she wrote in a testimony submitted to the council hearing back in December.

The CFB also responded to these negative claims, saying that they had been working on educational efforts throughout 2020, and in January launched a formal public awareness campaign on their site.

And with February 2 less than three weeks away, it seems likely that the city will stick to its original plan to implement RCV in the special election.

So, voters, study up!

This story first appeared in KCP sister site Queens County Politics.