Every day for the last month of this pandemic, essential black and brown workers have braved the city, riding in buses and trains to go to work, pulling double shifts and overtime, and showing up so that most of New York City could stay home.

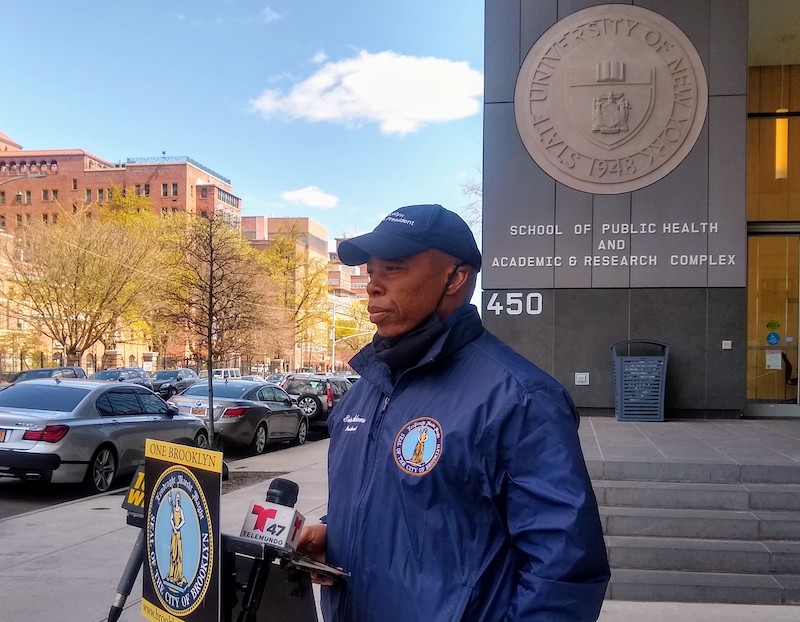

And Borough President Eric Adams, standing in front of State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Medical Center on a windy Saturday afternoon, demanded the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) get more personal protective equipment (PPE) for essential workers, and service black and brown communities that are disproportionately affected by the coronavirus.

This comes after statistics released earlier in the week showed that African-American and Latinx people were being affected at higher rates, making up just over 60 percent of COVID-19 deaths. Some people in these neighborhoods posited that the statistic was unsurprising given how disenfranchised their communities are.

According to labor force statistics from last year, Blacks/African-Americans were likely to be in occupations like postal services, clerks, janitors, security guards or surveillance, and healthcare support; while Latinos were likely to be cooks and food preparers, in construction, maintenance, packagers, and garbage or recycling collectors among other things. Many of these occupations continued to operate as essential jobs during the COVID-19 lockdown.

“We sent over 60 percent of the population of essential employees that are black and brown. Grocery store employees, transit employees, correction employees, 911 operators, nurses,” shouted BP Adams at the press conference. “We sent them into the danger zones and we said service the city while those who can telecommute and are affluent stay home.”

A 2018 study of workers said black and brown employees were significantly less likely to be able to afford work-from-home.

Wayne Neckles, a security officer at the Museum of Natural History in Manhattan who lives in East Flatbush, noted how he still reports to work to maintain and secure the artifacts and exhibits while the health pandemic rages on.

He said that during his daily commute, “The train isn’t clean with gloves and masks and food all over. It’s terrible. They give such nice fancy story on TV, but it’s different when you’re in it.”

Neckles described how the buses are taped off from the front, effectively pushing people closer together towards the middle and back of the vehicle. He said that people, covered in PPE or not, have no other choice but to muscle through.

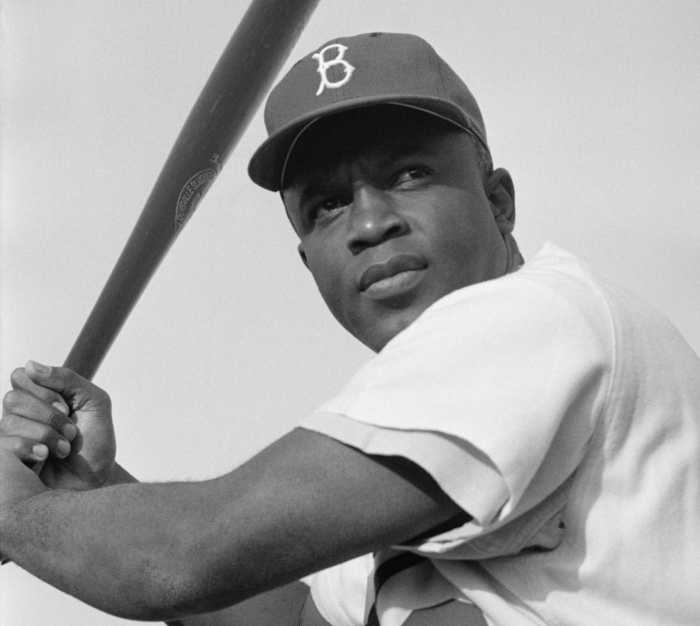

“The poverty level is based on the community you live in but this goes way back for us,” said Neckles about black history.

In a journal about race and health, findings last year explained why a community’s location can affect well-being.

The published journal said racial residential segregation causes health disparities. Research shows it reduces economic status, access to quality education, and creates concentrated poverty in certain neighborhoods.

These concentrations lead to things like low-quality housing, environmental factors, exposure to physical and chemical hazards, and chronic stressors. Plus, segregation adversely affects the availability and affordability of proper healthcare.

At a press conference held yesterday on Easter Sunday, Mayor Bill De Blasio said, “We see a clear disparity in the impact, who’s been hit hardest, communities of color, lower-income communities, immigrant communities, folks who are vulnerable already because they haven’t had the health care they needed and deserve throughout their life. We cannot accept this inequality.”

De Blasio said by the end of next week, testing sites will be in East New York in Brooklyn, Morrisania in the Bronx, Harlem, Jamaica in Queens, and the Vanderbilt Clinic on Staten Island.

Unfortunately, it’s not just New York City, but other places like St. Louis, Missouri and Chicago, Illinois with predominantly black and brown populations, that are seeing spikes in COVID-19 death rates.

This suggests that this is a systematic problem for several reasons, the second being the prevalence of underlying health conditions in these communities.

“They don’t eat right,” said Margaret Francis, who runs the Silver Crust Restaurant, 660 Utica Avenue in East Flatbush.

She was standing behind a buffet with steaming trays of Jamaican food from end-to-end of the small restaurant. The chairs are piled on top of the few tables in the place. She said that she doesn’t really feel in danger at work, she just keeps her distance from people and changes her gloves often when handling the food.

Her and her colleague said that their neighborhood’s health problems are because of people’s diets when asked what they thought of the COVID-19 death statistics.

Black Americans have higher rates of asthma, hypertension, and diabetes according to the National Institute of Health. The health journal stated that, “there are elevated rates of disease and death for historically marginalized racial groups, blacks (or African Americans), Native Americans (or American Indians and Alaska Natives) and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders, who tend to have earlier onset of illness, more aggressive progression of disease and poorer survival.”

“Here we are potentially a month later into the virus and we’re just getting our first testing center of this magnitude in Flatbush. Think about that. Unimaginable,” said BP Adams.

Governor Andrew Cuomo announced five new testing facilities, including a drive-through one at the Sears Parking Lot at 2307 Beverly Road and a walk-in facility in Brownsville by appointment only.

DOHMH didn’t comment in time for this article.