A research hearing was held on Tuesday for the Commission on Property Tax Reform, where experts discussed the long and short-term implications of changes to New York property tax law.

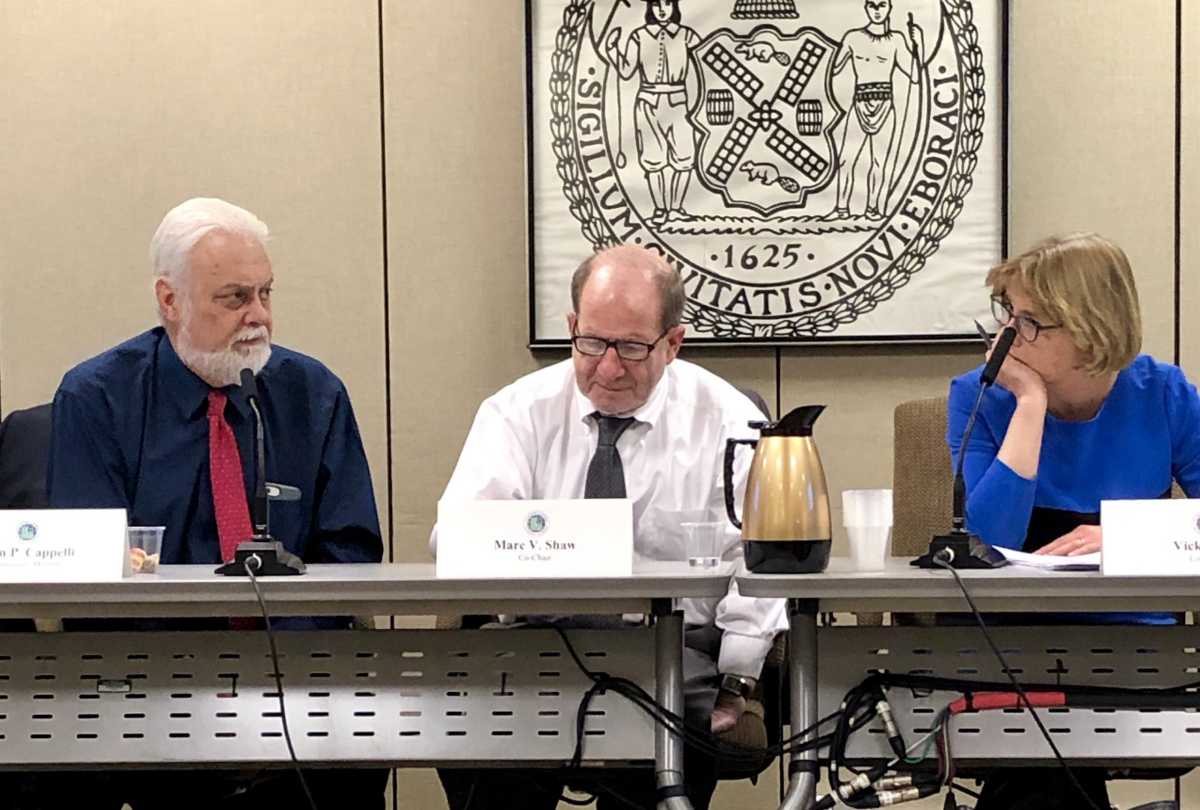

The hearing was held at the New York City Housing Authority’s headquarters in Manhattan and was co-chaired by Vicki Been and Marc Shaw. Andrew McLaughlin, the executive director of the city’s Rent Guidelines Board, served as one of the experts on property taxes at NYCHA.

“We are very fortunate to have three people that we’ve called upon to help us with this question about how property taxes affect both the values of homes, the values of rental buildings and the rents within those buildings,” said Been.

One aspect of the tax system discussed at the hearing was how changes to the current procedure for valuations could impact both owners and tenants of multi-family buildings that contain rent-stabilized units.

“Generally speaking, multi-family buildings with six or more units built prior to 1974 are subject to rent stabilization,” according to McLaughlin. “However, multi-family buildings built after 1974 can also contain rent-stabilized units… [and] newly constructed dwellings…could elect to receive real estate tax exemptions in exchange for placing units in rent stabilization…for a specified period.”

Under the Real Property Tax Law, new dwellings could receive exemptions for rent stabilization units for 10 to 25 years, and there are currently 88,000 units out of 966,000 rent stabilized housing units across the city that would qualify for that abatement, according to McLaughlin. Rent stabilized units represent 44 percent of the city’s entire rental stock and about 30 percent of all renter and owner housing units.

Each year the RGB is required by law to review the economic conditions of the residential real estate industry in the city, real estate taxes and sewer water rates, gross operating maintenance costs, availability of financing (effective rates of interest) and overall supply of housing accommodations and vacancy rates.

The RGB is also required to examine relevant data from the current and projected cost of living indices for the affected areas.

One of the studies that annually measures the real estate tax cost for owners of rent-stabilized buildings is the Price Index of Operating Costs (PIOC).

The PIOC measures changes in the price or cost of purchasing a specified set of goods and services used in the operation and maintenance of rent-stabilized apartment buildings in the city. The tool is similar to the Consumer Price Index, which measures inflation, and it currently accounts for 30 percent of the overall CPI, making it the largest operating and maintenance expense for owners.

The PIOC cost components since March 2018 include taxes (29.9 percent), labor costs (16.7 percent), fuel (6.4 percent), utilities (10.3 percent), maintenance (17.9 percent), administrative costs (13.6 percent) and insurance costs (5.1 percent), according to McLaughlin.

“A decline in real estate taxes will lessen the rate of growth of the overall PIOC for at least a single year,” said McLaughlin. “However, the impact would be dependent on changes in the cost of the other six expenditure components.”

If there were a decline in taxes, the immediate one-time effect would be a tax bill that is lower than the year before, according to McLaughlin. There would also be a longer-term effect of lowering the relative importance of taxes as a proportion of overall operating and maintenance expenses.

McLaughlin would not make an absolute conclusion, but said, “a potential decline in real estate tax expense…would dampen any upward change in renewal-lease adjustments, for at least a single year.”