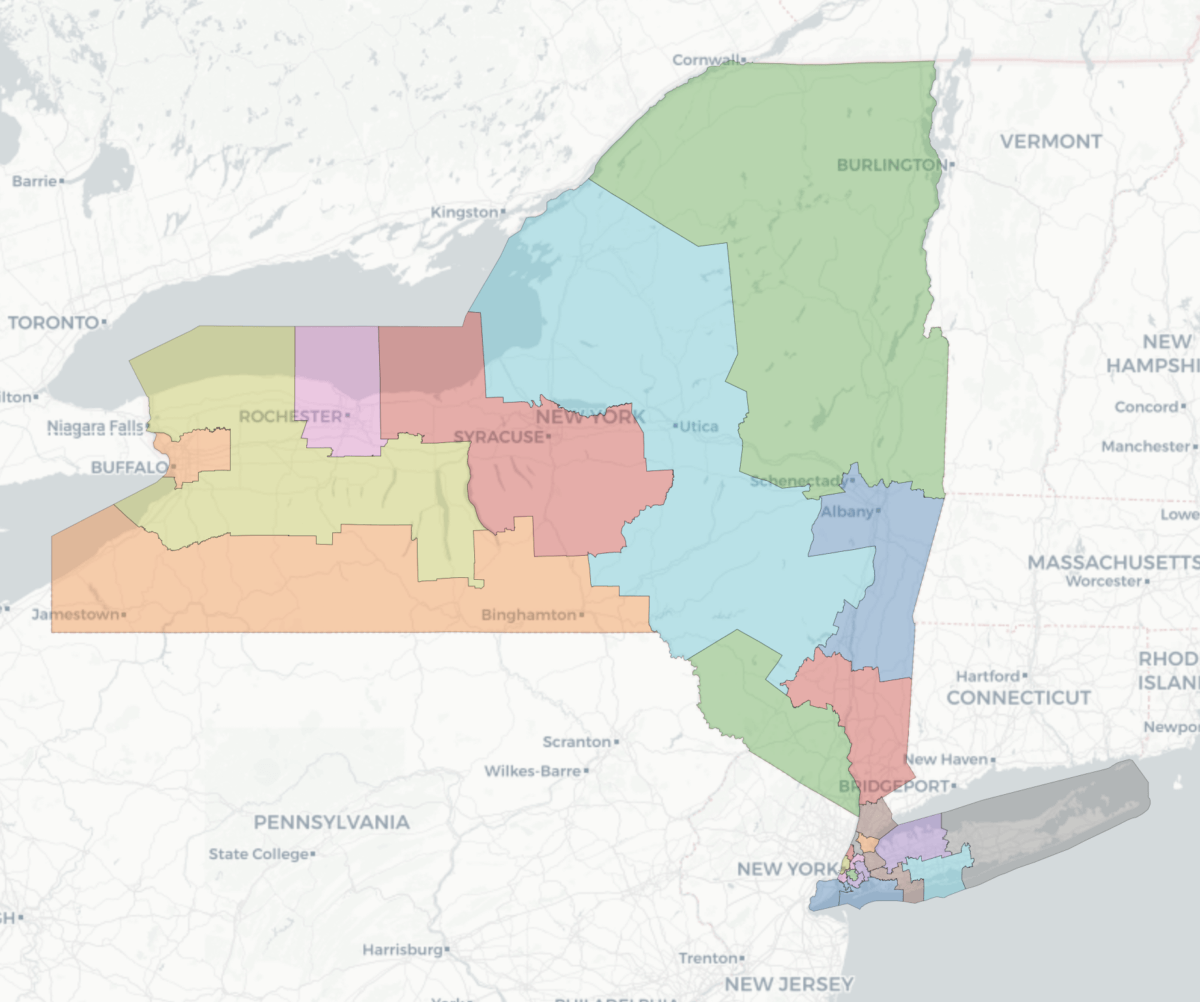

On January 24, the New York State Independent Redistricting Commission announced that it failed to agree on redistricting plans to submit to the legislature. As a result, the Democratic majorities in the state Senate and Assembly are positioned to draw their own maps, subject to Governor Hochul’s approval. The Republican state party chair is already talking about challenging those plans in court. A court challenge, however, likely would be an uphill battle.

Courts repeatedly have dismissed challenges to redistricting plans enacted by the New York State Legislature. In FAIR v. Weprin, a political gerrymandering challenge brought against the 1992 state assembly redistricting plan, a federal district court held that the enacted plan didn’t deprive Republicans of their opportunity to influence state politics. Also in 1992, in Wolpoff v. Cuomo, the New York State Court of Appeals upheld a state senate plan that split counties across the state, despite a prohibition against unnecessarily splitting counties. In upholding the plan in that case, the court determined that the legislature “complied with the State Constitution as far as practicable.”

After the decennial censuses in 2000 and 2010, successive challenges were brought to the New York State Senate plans the legislature had enacted. Plaintiffs’ alleged population malapportionment claims were rejected by a federal court. The courts in those cases also deferred to the legislature’s judgment.

In 2012, the New York State Court of Appeals held in a challenge to the increase in the size of the Senate that “acts of the Legislature are entitled to a strong presumption of constitutionality and we will upset the balance struck by the Legislature and declare the [redistricting] plan unconstitutional only when it can be shown beyond reasonable doubt that it conflicts with the fundamental law, and that until every reasonable mode of reconciliation of the statute with the Constitution has been resorted to, and reconciliation has been found impossible.”

The state constitutional amendment enacted in 2014 requires the legislature to follow criteria that include achieving stricter population equality, not discouraging competition, and not favoring or disfavoring incumbents, candidates, or political parties. The legislature also must consider the maintenance of cores of existing districts, political subdivisions, and communities of interest.

The constitutional criteria were not ranked in priority order. Mapmakers are left to balance conflicting criteria the way they best see fit. These are the kind of policy-making decisions that courts look to the legislature to make.

To succeed, a challenge against this year’s redistricting plans in state courts would have to demonstrate to a court, “beyond a reasonable doubt,” that the plans egregiously violated state constitutional standards.

Of course, courts also can step in and draw maps when the Senate, Assembly, and governor fail to agree on maps. Courts, however, generally give the legislature more time to draw a map or fix a problematic one before stepping in and drawing its own map. This happened in 2012 after Albany leaders failed to come together on a congressional plan.

A likely scenario ahead for redistricting is final action by the New York State Legislature by mid-February and use of those maps in the 2022 elections. Any court challenges could be expected to take too much time to be resolved before those contests are held.

Jeffrey M. Wice is an Adjunct Professor/Senior Fellow at New York Law School and an expert on redistricting.