A proposed ban on flame retardants in New York State is riling up not only local businesses and fire safety advocates but also New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) tenant leaders worried about an increase in fire-related deaths and injuries in housing developments.

Flame retardants are chemicals used in everyday electronics, like TVs and cell phones, and household products, like children’s toys, treadmills, and couches or mattresses. They protect against a fire starting or prevent spread of a fire by reducing the energy available, said the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS).

The ban, or S.4630-A/ A.5418, would stop the sale of products that have fire retardants in residences since they might be harmful to the environment. State Senator Todd Kaminsky (D-Long Island) sponsored the bill and the Child Safe Products Act. Flame retardants were among a list of “roughly 100 chemicals deemed to be dangerous to children” and told Post-Journal that that was “well-documented” back in 2019.

“I have a 10-month-old child. I watch him put everything he can get his hands on in his mouth,” said Kaminsky in the article.

The chemicals in fire retardants are stubborn and not easily broken down over time. They can affect the environment and “bioaccumulate,” or build up in people and animals. The biggest concern is the potential health problems, like endocrine and thyroid disruption, impacts to the immune system and reproduction, cancer, and adverse effects on fetal and child development, said the NIEHS.

That being said, the NIEHS notes that they are still studying flame retardants’ effects and are interested in conducting research that will help companies develop safer alternatives.

Chemists, such as Matt Blais, director of Research and Development of Fire Technology Department at Southwest Research Institute, maintained that fire retardants are already safe and life-saving in the case of a fire.

“There’s a lot of thought in the community that every chemical is bad, not realizing that everything around us is a chemical,” said Blais. “There’s a group of people that think the chemicals have perceived health risks, therefore it’s not worth the health risk to have the flame protection. Every time we study these things we find that the health risks are way overstated and that’s kind of bad because the fire risk is not overstated. Fire kills people all the time.”

Blais also said that while all fire smoke is toxic, when fire retardants are present, smoke develops more slowly and gives people more time to put the fire out.

The NIEHS said that fire retardant chemicals, like bromine for example, were more prevalent in consumer products from the 1970s and many have since been “removed from the market or are no longer produced.”

“The deadliest year in New York City for fires was 1970, when 310 people died in fires,” reported the FDNY.

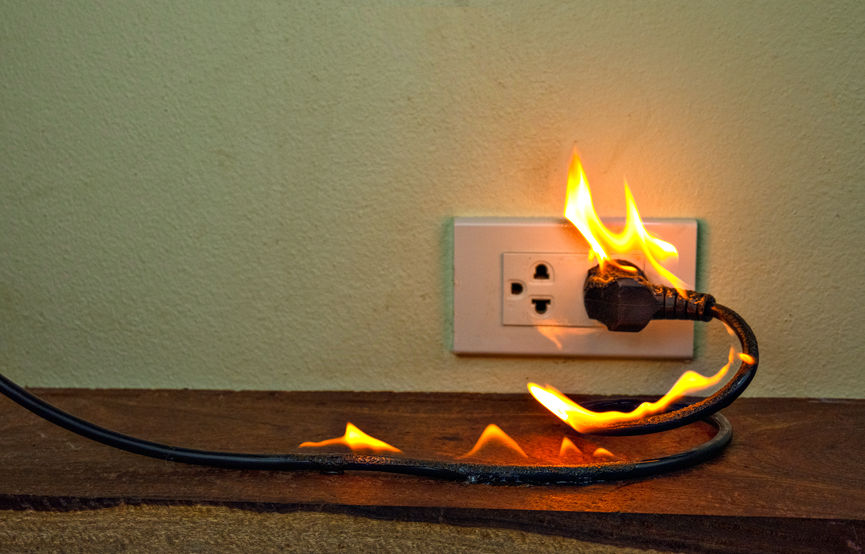

FDNY data from January 2021, provided to PoliticsNY, indicates that fire deaths have at least been trending down in decades since. There were 63 fire deaths in 2020, 66 in 2019, and 88 in 2018. Fire marshals determined the top cause of last year’s fire deaths was electrical.

An FDNY spokesperson said the department doesn’t comment on pending legislation, but the Firemen’s Association of the State of New York (FASNY) issued a statement of support of Kaminsky’s bill.

FASNY said that they have made the protection of volunteer firefighters from health risks associated with fighting fires a major priority, and in their own independent study, have found increased dangers of cancer associated with chemical flame retardants.

“These increased health risks are why FASNY believes that this bill must be passed – to not only protect our volunteer firefighters, but also the public at-large,” stated FASNY.

That still hasn’t convinced some NYCHA residents and people in the scientific community though.

“The threat of fires is something we live with every day as public housing residents,” said Claudia Coger, president of the Astoria Houses Tenant Association. “It is deeply troubling that lawmakers would consider taking action that could make it easier for fires to spread and even more difficult for residents to escape in a life-or-death situation.”

Paulette Shomo, former president of the Marble Hill Tenant Association, agreed that fires are a major concern in public housing.

“When it comes to fire safety and response time, every second matters, and it’s clear that this legislation would significantly reduce the amount of time NYCHA residents have to get out of our apartments, threatening our safety and putting seniors at especially high risk,” said Shomo.

The American Chemistry Council (ACC) and a broad coalition of chemistry and safety groups wrote a letter to New York State legislators on April 23, and argued that the ban would “adversely impact product safety for New Yorkers and would put manufacturers, retailers and small businesses in our state at a competitive disadvantage.”

“This bill proposes removing flame retardants from commonly used electronic products at a time when more people are spending time in the home,” wrote the coalition. “Assessing a product safely is more than simply noting the presence of a chemical substance in a formulation.”

The coalition also said that vulnerable populations in cities, like Black and Brown neighborhoods and seniors, are at a much higher risk for fire deaths than anyone else. Blais said there tends to be older furniture and products in low-income households which causes more vigorous fires, and the buildings tend to lack the safety infrastructure, like sprinkler systems, necessary to protect disadvantaged residents.

Blais said the state ban wouldn’t have any effect on the people at risk just the new products being produced. Anything “used” would still have the fire retardants in them, said Blais.

“Chemical industries have responded to these complaints about fire retardants by making better fire retardants now,” said Blais, speaking about non-bio-available products that have molecules the human body can’t absorb.

The court hearing on the bill is on Monday, May 10.