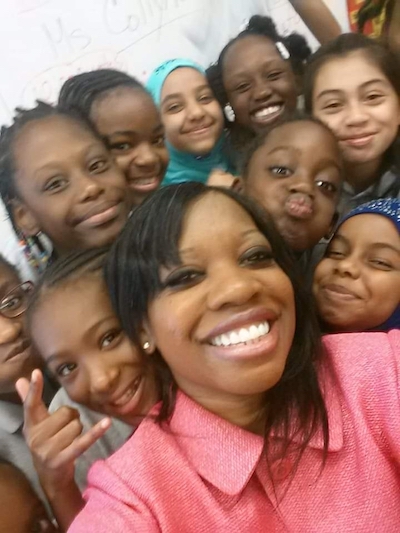

Community activist Renee Collymore is one of nine candidates vying for term-limited Majority Leader Laurie Cumbo’s 35th City Council District seat.

“I’m running because this district needs proper representation and protection. I’m running because I am the candidate that has the most experience, the most achievement, and knowledge of this district than anyone. I’m born and raised here,” began Collymore.

The district includes Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, and Prospect Heights, portions of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, Downtown Brooklyn, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and Vinegar Hill.

Collymore’s father, Cecil, was a Bajan immigrant while her mother was a Southerner. She said her parents both moved to New York in the 1940s and hustled vigorously through various odd jobs to support themselves before purchasing a plot of abandoned, crime-ridden land and housing in the Fort Greene and Clinton Hill neighborhoods. Eventually they opened a string of business and storefronts on Putnam Avenue between Grand and Downing Streets, said Collymore, that contributed to and cleaned up the community.

“The area was so destitute that no one even wanted to walk down that block, but there was a stretch of commercial storefronts for sale,” said Collymore. “My mom told my dad to buy that land.”

Collymore, a second-generation Brooklyn native, said there are several social issues that have plagued the district for decades, but housing more than anything needs to be addressed. She is particularly passionate about affordable housing and real estate issues because of her family’s history and believes that small mom and pop businesses are the “backbone” of any community.

She proposed an elimination of Business Improvement District (BID) tax liens on small businesses now, similar to how Governor Andrew Cuomo and Attorney General Letitia James put a hold on the annual tax and water lien sale for homeowners on September 4.

“I hosted meetings about the BID and how the first wave gentrification was coming through the elimination of small businesses on Fulton Street,” said Collymore about past efforts to educate Black and immigrant-run business owners against raising rents.

“We are a thriving and creative district,” said Collymore about the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis to housing and rental prices. She said as a child she’d already experienced ‘white flight’ when the majority of her neighbors in Fort Greene left for Long Island because Black families moved in during the 1970s, so she isn’t worried about upper-class renters or gentrifiers leaving the borough.

She vehemently disagrees with the overdevelopment and gentrification of what was once a primarily Black and Brown district. “We have to make sure that the people of this community are preserved, the history of Black people in this community must be preserved,” said Collymore, who fought hard to rename the block her family-owned after her father.

On the subject of public housing and New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) developments, she said she’s battling quality-of-life issues at the moment in Fort Greene. “I’m fighting for a renovated bathroom on the Myrtle Avenue side, on the north side of the [Fort Greene] park. The bathroom is disgraceful. It’s pee-ridden, homeless people go in and there and shower. There’s drugs in there, and children and seniors have to use that bathroom,” said Collymore.

She pointedly said it’s not about getting a tenant association endorsement because many of them are already bought by the establishment. “I’m fighting because those people don’t have help,” said Collymore.

Collymore said she isn’t against all major real estate developments though.

She said she likes the focal point that Brooklyn Navy Yard has become and Wegman’s has helped end a food desert by providing easily accessible organic foods and produce to the surrounding neighborhood. However, she hates that they tore down Admiral’s Row, which used to consist of stately mansions over 150 years old, for a parking lot. “I hate that it couldn’t be saved,” said Collymore, “It could’ve been a museum.”

“Listen if you want to make this like a tourist community, then you say that, and then we work toward how we can get that done without pushing people out. Because even with the Barclays Center, I was in that fight,” said Collymore, who disapproved of the people who lost homes and property when the stadium was being built in 2010.

Collymore’s family recently sold the businesses, her father having passed and mother getting up in years. She and her mother still reside in their residential properties in Clinton Hill, said Collymore.