The death of George Floyd at the hands of police sparked a nationwide and global Black Lives Matter movement of protests, demonstrations, and riots with Brooklyn being no exception. People have flooded the borough’s bridges, streets, monuments, plazas, and public squares with outrage and a ringing demand for social justice for months during the equally long and draining COVID-19 health crisis.

This isn’t, however, a recent phenomenon.

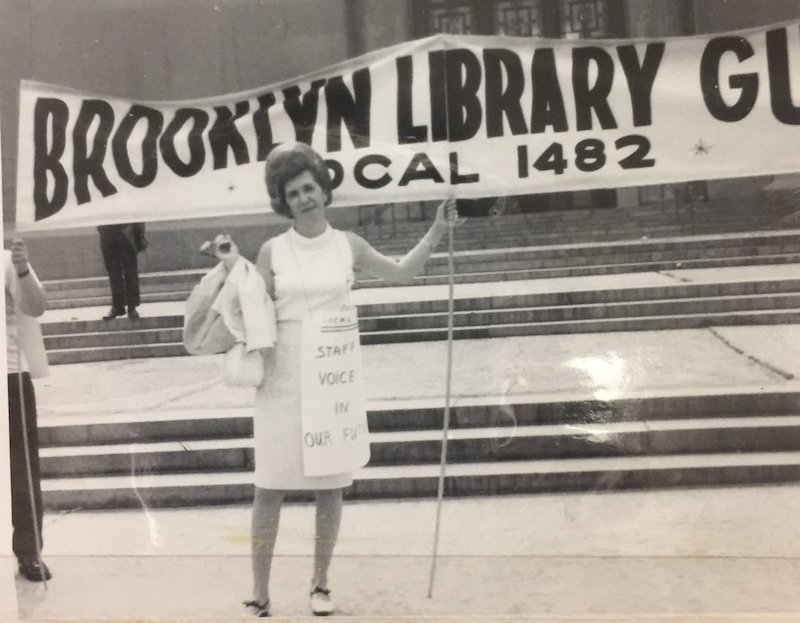

Brooklyn has a long history of the masses, whenever necessary, making their voices heard for a cause. They stomp across the Brooklyn Bridge or don protest signs in front of the Brooklyn Public Library (BPL). They strike. They yell. They pack the steps of Borough Hall or its subways and overrun Cadman Plaza park.

“Not only has New York City been at the center of many movements for justice across its history, but we have seen the need for racial and policing justice changes up close, from Eleanor Bumpers to Eric Garner,” said Public Advocate Jumaane D. Williams.

Williams was infamous for his occupation, arrests, and demonstrations in and around Brooklyn as a councilman before becoming the official advocate of the city. This year, in addition to many other causes, he led a group of hundreds across the Brooklyn Bridge to rally for reallocating funds from the police department to youth and social services.

Crossing the world’s first suspension bridge, in particular, seems to be a favorite historical landmark for activists. Designed by John Roebling in 1869, the bridge is considered a 1,595-foot “feat of 19th-century engineering” made of twisted steel cables for wire and towers made of giant limestone, granite, and cement. As many as 20 workers were killed during its construction, and many more suffered from decompression sickness, or a disease where nitrogen bubbles up in human tissue.

Nonetheless, the site has been home to protests for several causes, including the most recent calls for police to stop shooting unarmed Black men, like Amadou Diallo in February of 1999. Or choking them, like Eric Garner in December of 2014.

“New York prides itself as a progressive leader, and the people of the city are speaking out to push their government to live up to that. We know protest allows voices to be heard, and occupying prominent locations in this City will force those willfully ignoring the issues, to see,” said Williams.

“These designated areas or routes for various marches in the Black Lives Matter Movement and other social justice actions are purposeful,” said President of Black Lives Matter Brooklyn Anthony Beckford, who is also running for city council in the 45th District.

“It is not just based on accessibility, but also based on the history and symbolism of marches that have occurred before. For example; walking across the bridge to many is compared to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. There are many stories that the people share with each other of their experiences in each of these locations.and that makes those who have not started a march or ended a march there motivated to show up at the next action to be a part of the moment,” said Beckford on what makes these kinds of protests iconic.

This year also saw large political, cultural, and racial justice gatherings, like police reform rallies with Brooklyn electeds at Grand Army Plaza and Juneteenth celebrations in front of the main BPL branch downtown.

“At the confluence of several major thoroughfares and neighborhoods, Grand Army Plaza has always been a gathering place for Brooklynites. Its location between two iconic Olmsted and Vaux designs, Prospect Park and Eastern Parkway, cemented its status as a hub for the Brooklyn community from the beginning,” said BPL archivist Diana Bowers-Smith. “With the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Brooklyn Museum and of course, BPL all nearby, the plaza is indelibly woven into Brooklyn’s civic life–which of course includes protests and political activity.”

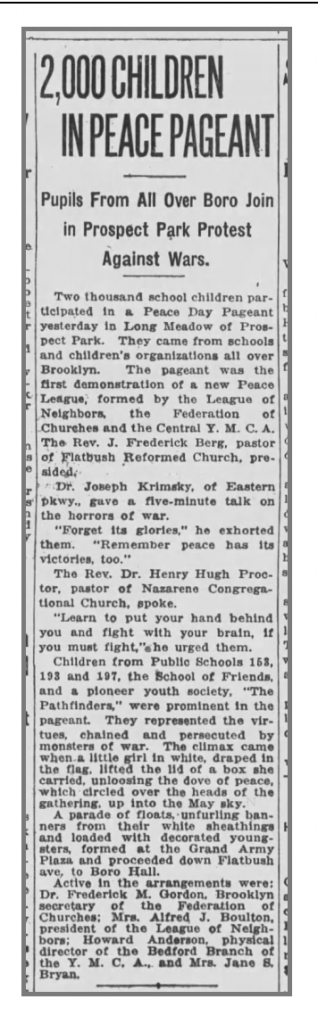

Bowers-Smith said historically there have been numerous political demonstrations held there, from a children’s peace pageant and a cleanup Brooklyn parade, both in 1926; to a World War I veterans rally for bonus pay in 1931; to a rally against former President Ronald Reagan’s visit to Bitburg Cemetery in 1985.

“Even the library’s own staff have occasionally taken to the steps,” said Bowers-Smith.

The BPL, like many other neutral spaces, sustained some damage to its property during the current protests gripping the city.

Even so, Bowers-Smith said that BPL “embraces and welcomes such public use of both Grand Army Plaza and the adjoining plaza in front of Central Library as part of its mission to provide the people of Brooklyn with free and open access to information and its vision to be accessible 24 hours a day in ways that reflect the diverse and dynamic spirit of the people of Brooklyn.”

Nowadays new gatherings places, like the Barclays Center Stadium plaza and Black Lives Matter street murals, have been added to significant areas of Brooklyn and celebrated for their roles in Brooklyn’s civic engagement.