It’s hard not to cringe at Bed Stuy’s newest mural. That’s the intended reaction.

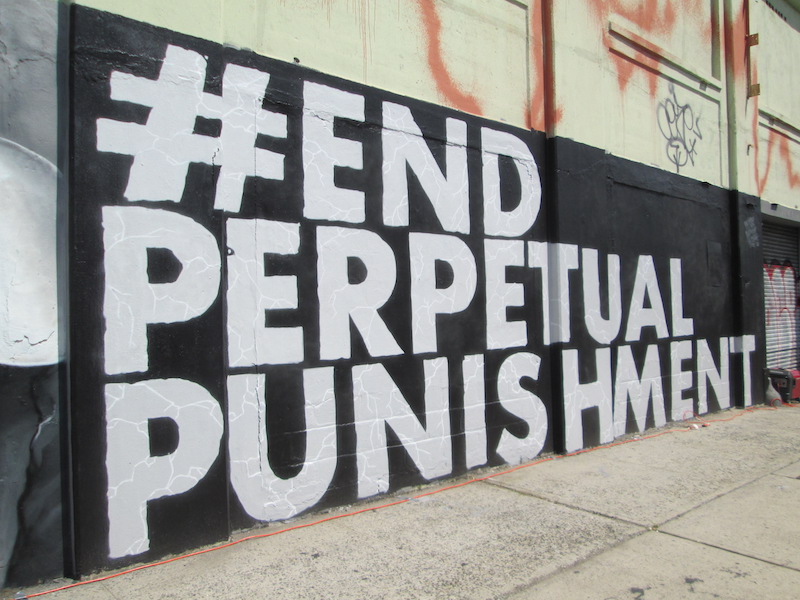

Drivers along Atlantic Avenue and Perrey Place will be greeted with the image of two water fountains: one labeled “white,” and the other labeled “criminal record.” To its right, in massive block letters each the height of a grown man, the hashtag “END PERPETUAL PUNISHMENT.”

The mural, and the broader #EndPerpetualPunishment movement, are the product of Next100, a progressive think tank. The organization was joined by a host of Black elected officials: Borough President Eric Adams, Councilmember Robert E. Cornegy (D-Bedford Stuyvesant, Northern Crown Heights), Assemblywoman Tremaine Wright (D-Bedford-Stuyvesant, Northern Crown Heights), and State Sen. Zellnor Y. Myrie (D-Brownsville, Crown Heights, East Flatbush, Gowanus, Park Slope, Prospect Heights, Prospect Lefferts Gardens, South Slope, Sunset Park) all came to express solidarity with Next100’s aims.

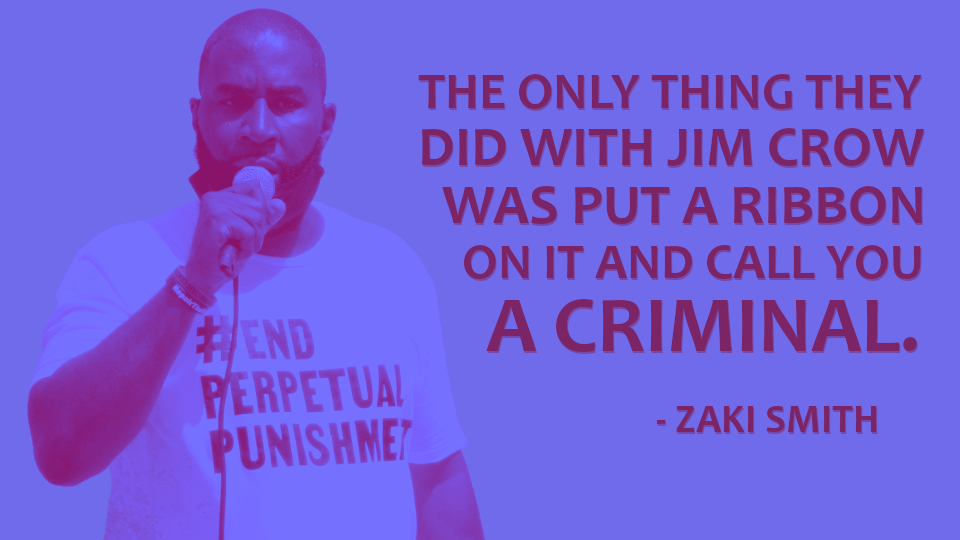

But the day belonged to the mastermind behind the mural: Next100’s criminal justice czar, Michael “Zaki” Smith.

Smith himself was incarcerated for a minor crime, and lost his job at a New Jersey high school due to his criminal record – even though he had taught there for five years, and even though he had completed his prison sentence.

“From then on it ballooned into this investigation for me,” Smith told the crowd. He began working with various nonprofits to advocate for the rights of people like himself. He found what most already know – the statistics for formerly incarcerated people are grim. Many struggle to find work, or graduate, or even stay out of prison.

Smith spearheaded the #EndPerpetualPunishment campaign, but he also serves as the face of the movement. Quite literally: the man depicted drinking from the “criminal record” fountain is none other than Zaki Smith.

“I need shock value,” Smith explained of the mural’s invocation of Jim Crow imagery. “The only thing they did with Jim Crow is put a ribbon on it, and call you a criminal.”

One man who narrowly avoided being victimized by “the new Jim Crow” was Borough President Eric Adams. Adams and his brother were arrested for a misdemeanor at age 15 in South Jamaica. If that criminal record had come to light, Adams noted, he never would have been allowed into the NYPD; he never could have formed 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care; he could never even dream of becoming an elected official.

“This wall here is representative of my life’s work,” Adams said. “If my record was not sealed, none of this would have existed.”

Adams says that while he made something of his life after his arrest, other black men weighed down by criminal histories have not been so lucky – and society is the worse for it.

“The destruction of the lives of people who were formerly incarcerated is destruction of their input entirely,” Adams said. “We are all impacted.”

Other elected officials at the events saw the criminal justice system from the other side. Robert Cornegy’s journey to City Council started at Rikers Island, where he worked in social services – a misleading name, in his estimation.

“I saw there were no social services,” Cornegy said. Nothing regarding reintegration into society, anyway. His attempts to reform Riker’s from the inside, making it easier for inmates to seek out his services, were met with resistance. He hopes murals like this one will raise public awareness of the stigma that haunts those who’ve been arrested.

While discussions of the carceral state often focus on black men, women also suffer the stigma of “perpetual punishment.” Tremaine Wright noted that while working as a lawyer for women at Rikers, she saw firsthand how family units were dismantled by the prison-industrial complex. She hopes projects like this raise awareness and “chip away at the boulder” blocking the formerly incarcerated from reintegrating into their communities.

“We got a nice stop sign here,” Wright told the crowd, “so that message is about to get out.”

But the path from “raising awareness” to concrete change is tricky, as State Sen. Myrie noted. He’s worked closely with Zaki Smith on issues like these, and just last year co-sponsored a bill that automatically expunged low-level marijuana possession charges from the records of thousands of New Yorkers. It’s given him insight in how difficult meaningful reform can be.

“We double jeopardize people for being victims of a racist critical justice system,” Myrie said. “Any dismantling [of that system] will face backlash from those who want to keep the status quo.”

It’ll be a gargantuan task – but Zaki Smith knows from firsthand experience how important it is.

“70 to 100 million formerly incarcerated people experience this same punishment,” Smith said. “We have paid our debt to society. What more do we owe?”