Grandma’sgoingtobeokay. Grandma’sgointobeokay. Grandma’sgoingto be okay, but she can’t breathe.

I’m not fond of needles or testing. I don’t like doctors. But, no one can really afford to be the one in the room who sneezed and killed the matriarch.

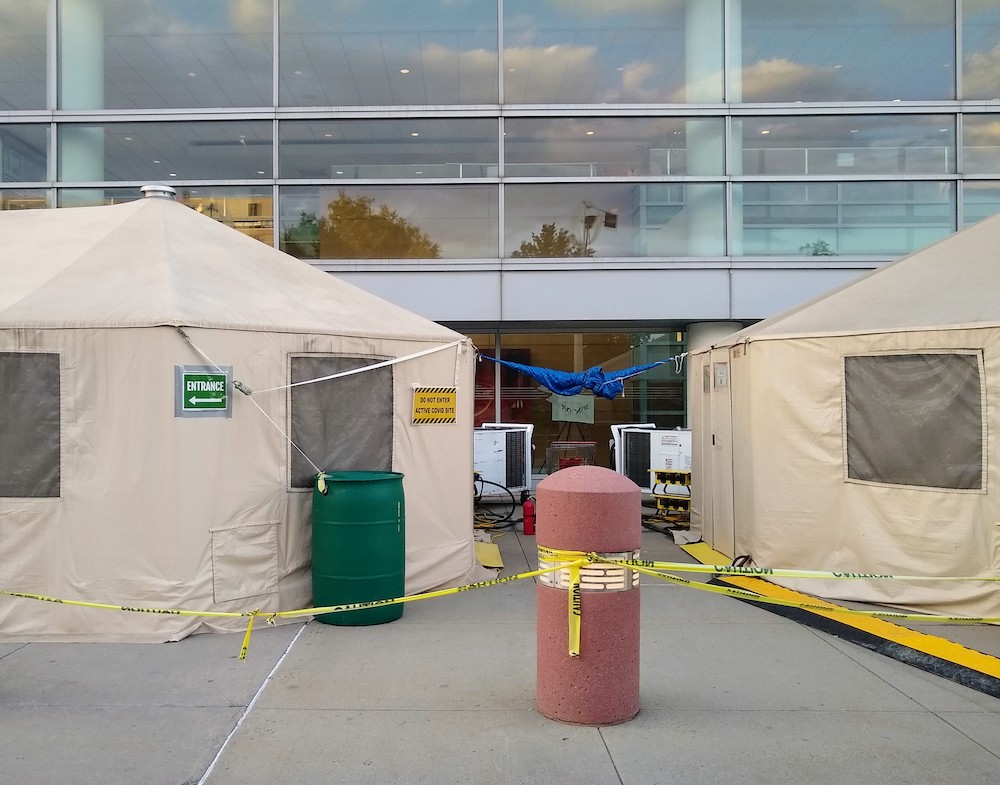

Kings County Hospital looms over me while I wait outside a yellow alien tent in a snaking line to get tested. My grandma was a head nurse here for over 30 years.

She told me that after she graduated and took the test to be a nurse, she’d check the mailbox everyday to see if she got the job. She said when I graduated in 2018 and filled out all these applications to be a journalist with no real response, “It’s fine. Just keep checking the mailbox and it’ll come.”

Over the phone, I cackled and had to tell her it’d probably come in an email, but I appreciated that she had nothing but faith in me.

Judging by the way she’d tend to my torn up knees as a kid, I imagine she was quick, tough and fair, gentle when needed, and dismissive with a laugh when nothing was life-threatening. I never saw her in her prime. She had already had an onset of diabetes and heart problems by the time I was born and had retired from a career in nursing.

Sometimes when I talk to her over the phone now, she can’t remember which one I am. Grandma’sgoingtobeokay.

A large doctor type, all masked up, invites me through this tiny tent door. It’s bigger inside than I thought it’d be with sectioned off little booths and at least three stations with computer screens. He said to rub hand sanitizer onto my gloves and stand on the marked spot. The slight distance makes it hard to hear over the large black and yellow ventilating tubes in the corners. The masked figures, huddled into their computers, ask over and over for ID so they can figure out who I am. For a moment, I think about being a Long. My grandmother going to the hospital to save lives, my grandfather coming home from the airforce to find another job at the airport.

“My name’s Ariama C. Long. I’ve been to Kings County before. I should be in there,” I said. I’m instructed to follow a marked blue line on the floor until I get to the end, like Dorothy kicking at golden bricks. On this end, a brown-skinned woman smiles underneath her mask because the faint lines around her eyes crinkle. She asks me my name again. I’ve stopped paying attention to words though. My heart rate’s picking up.

She sticks another identifier on me and points to another flapping tent door, which another an even taller doctor type in a full-bodied, light blue protective suit has to bend down to step through. He moves smoothly, accustomed to this height difference. I wonder if he was ever a lithe brown child told he should be playing basketball. We leave the first tent, idle outside for a second, and then enter the main hull of the beige tent.

There’s more humming, more space, more suited types. The tent door snaps closed behind us.

He asks me my name again.

The lengthy table to the left is organized with blood canisters and butterfly needles and blah blah medical equipment. Grandma’sgoingtobeokay.

I realize they’re all staring because I haven’t moved yet. I’m directed to sit down, on the far side of the ship, in a plain metal folding chair. The woman touches my mask and tries to tip my head back, after asking my name again. She takes a long clear looking stick and wants me to look at the wall straight ahead like a mummifier preparing to scramble someone’s brain with a heated iron. The swab feels like it touches the base of my brain, everything tears up, it burns, and I can’t breathe. Grandma’sgointobeokay. Grandma’sgoingto be okay, but she can’t breathe. George Floyd couldn’t breathe.

The suited figures guide me to the bloodletting station and ask me my name again. I close my eyes to think about anything other than being stabbed and take deep breaths.

The ordeal is over and I’m instantly forgotten for the new face that’s wandered in the tiny door for testing.