Days prior to George Floyd’s death, downtown Brooklyn was comparable to a ghost town with fear of contracting the coronavirus being the biggest threat. The stillness abruptly changed as the borough’s streets were suddenly flooded with mobs of people as they converged at Borough Hall and the Barclay’s Center over the weekend.

They fanned out throughout the residential and commercial streets in anger, in solidarity, and in some cases violence, much like a dreaded and unstoppable virus – all due to the most recent incidents of police and social brutality targeting black people. Their infectious and impassioned anger catching whatever came into their path, namely police or property.

As of Sunday, public information said that the majority of arrests were in Manhattan and Brooklyn totaling 345 people, 33 police officers injured, and 47 police vehicles vandalized.

It was on May 4 that the city rallied for Donni Wright, who was sat and callously kneeled on by a NYPD officer supposedly enforcing COVID-19 compliance orders. Raw frustration over these shut-in orders and videos of several more of these fraught interactions, compounded with the violent shooting death of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia and George Floyd’s strangulation by knee in Minneapolis, was bound to boil over.

In speaking with Brooklyn’s elected community organizers and people on-site at these gatherings, it appeared that the origin and leadership of the protests were identifiable at times, such as the Black Lives Matter organizers – and disturbingly unknown at others.

“When I walked from Borough Hall to the heart of the protests in Brooklyn over the murder of George Floyd, I reflected on the pain I felt for him,” said Borough President Eric Adams about the first protests downtown. “It is a pain we’ve felt, again and again, over the years, as we’ve watched countless Black people across this country fall victim to police abuse. Abner Louima. Amadou Diallo. Tamir Rice. Philando Castile. Sandra Bland. Freddie Gray. Eric Garner. Breonna Taylor. People whose lives were tragically cut short in the blink of an eye. The images of violence and destruction on our streets last night also brought back searing reminders of the past.”

Adams points out the black lives that have been taken by police for decades, stretching all the way back to the 60s and 70s in New York City, have taught him that racial inequality can quickly ignite into violence and disorder.

A notion that other city officials, like Assemblyman Walter T. Mosley (D-Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Prospect Heights, parts of Crown Heights, Bedford Stuyvesant) in primarily black and brown communities have echoed.

“Another African American man dies at the hand of a police officer. This headline too often rings true throughout our city’s and our nation’s history,” said Mosley. “The visual of strange fruit laying dormant on the cold concrete floor of my city is as American as baseball and apple pie. I walk in fear for the future of our current generation and for future generations of children of color we raise. Children we raise to have dignity and respect for themselves and their fellow man. But this familiar headline is a byline that remains to reverberate throughout my very being.”

Mosley said that the spirit for why blacks protest and the legacy of those who came before him shouldn’t be disgraced through looting and destruction, but used for positive and real sacrifice through a movement.

“We shut the 88th precinct down, it was closed,” said Sultan ‘Phyzique’ Malik, a tall fitness trainer with long dreadlocks that carried a boombox blasting N.W.A’s classic protest song “Fuck Tha Police” along Atlantic Avenue on Saturday evening. He’s been present at several of the early and more violent riots as well as the daytime protests. His voice had become strained and hoarse from tear gas used by police to pacify crowds.

In Malik’s instagram post he said, “Do we keep passively marching to no end; or do we take the fight to where it’s really at? At the source of the problem? I believe that the passive approach has shown to be ineffective in so many ways. All the marching…. ah I’m exhausted….[imagining] how the ‘real leaders’ of old had the drive to fight and fight [without] being tired! I’m tired!”

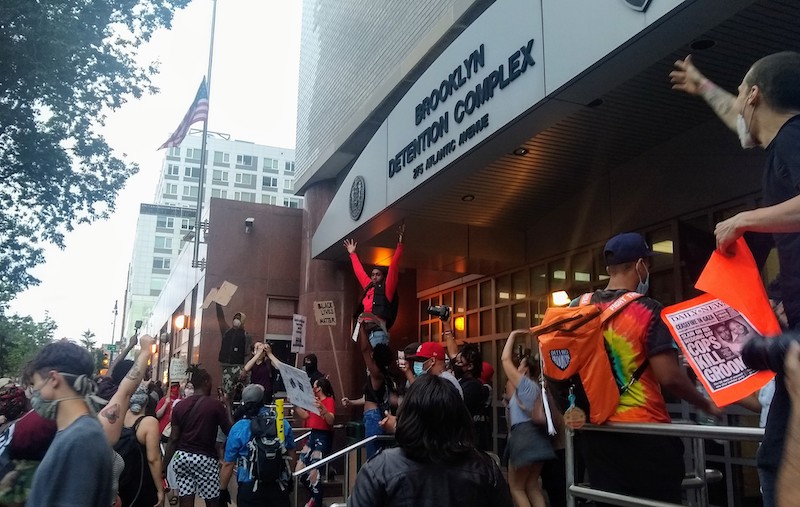

An abandoned sheriff’s car with the windows smashed in and curses spray-painted on the sides was visible on Court Street, where groups have roamed past daily with signs, chanting out loud and blocking buses or traffic. On Saturday, they walked briskly in a loop through the downtown district occasionally stopping to stand in the streets or sit on the steps of borough hall with police cars following at moments. At one point they gathered en masse outside of the Brooklyn Detention Center, where a brick was thrown at the lobby window.

Onlookers in cars usually honked in excited support while people in restaurants or hanging out of their windows clapped.

One resident in Prospect Heights, who lives on Smith Street and Warren Streets, said that she was aware of what happened in Minneapolis but honestly didn’t notice the protests that cropped up in the neighborhood until the weekend. Brooklynite’s on the other side of Prospect Park looked like they were just out to enjoy the calm weekend and take advantage of the sun.

Saturday afternoon’s vibe, however, did not mirror Friday or Thursday night’s rage.

Reportedly, most of the somewhat peaceful protests outside of Minneapolis, in cities and towns across the U.S, have become complete riots into the night. The people are visibly diverse, seemingly ranging from White, Black, Asian, Latinx men and women, and LGBTQIA+ sign holders.

Sources said that it seems like some people, possibly white anarchists, were only interested in violence against the police, inciting the tree and police car burnings, and the attack on the 88th precinct in Clinton Hill. A theory that could be supported as the acronym A.C.A.B., or All Cops Are Bastards, was seen spray painted in parts of the city. ACAB, according to the Anti-Defamation League, is a slogan of long-standing in the skinhead subculture, but can be racist or anti-racist depending on the context of the situation.

Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez said, “To any who have infiltrated these protests with the goal of sowing discord and distracting from their powerful message – please leave. Brooklyn is suffering and we don’t need you exploiting our pain for your own ends. To those who have lashed out in violence – Brooklyn can do better.”

Mayor Bill De Blasio commented on Saturday that it was certain that a substantial number of out of towners were arrested, but how many and other details would be released at a later date. “What we know for sure, and I’m hearing it from community leaders and elected officials, is they’re very dissatisfied by the reality of people, whether they’re from out of town or from other parts of the city coming into their neighborhoods and trying to dictate the terms to them. People who represent the communities of our city and the residents of our city are not joining negative and violent protests,” said De Blasio.

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo announced that State Attorney General Letitia James would review all actions and procedures of police and crowd actions during the protests in New York City and Brooklyn and issue a public report within 30 days.

“For 90 days we were just dealing with the COVID crisis,” said Cuomo in Saturday’s briefing. “On the 91st day, we had the COVID crisis and we have the situation in Minneapolis with the racial unrest around the George Floyd death. Those are not disconnected situations. One looks like a public health system issue — COVID — but it is getting at the inequality in healthcare also on a deeper level. And then the George Floyd situation, which gets at the inequality and discrimination in the criminal justice system. They are connected.”