A war is growing over the state of the city’s education system in the middle of a vast fiscal and health crisis while students continue to grapple with just getting a handle on the material, boredom, and the emotions of living in lockdown thus far.

Governor Andrew Cuomo announced last week a “Reimagine Education” advisory council, composed of prominent figures such as billionaire Bill Gates, which has sparked a fierce debate among local educators and officials about who ultimately decides for New York City’s schools. The financiers and the state or the city and its workers?

Here’s how educators and electeds pinpoint the realities of how remote learning has actually affected students and imagine their students’ futures.

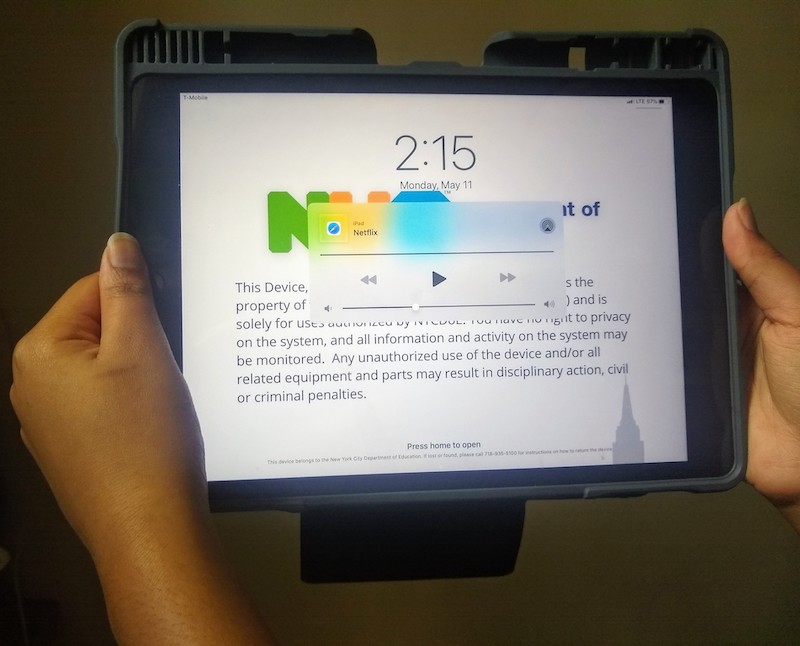

Schools Chancellor Richard A. Carranza made the first steps to supply the city’s students, about 1.1 million, with equipment for remote learning back in March. In an open letter to families, he acknowledged that the “dramatic transition” was in no way perfect, and couldn’t “replace a talented teacher in a classroom.”

“Remote learning has been a widely varying experience for both teachers and students, and more consistency is needed,” said State Senator John Liu (D-Queens), chair of the Senate’s NYC Education Committee. “Now that the devices have largely been distributed, the Department [Of Education] needs to strengthen its focus on actual instruction and learning by engaging teachers for best practices.”

Many educators have noted that it’s taken months since March’s rollout to adequately reach and equip the majority of the kids in the educational system with tablets and reliable access to the internet. Partly because there are so many, but also because of socioeconomic and emotional hardships that have crippled most students before and during this crisis.

“We’ve always been dedicated to making sure that our young people got the best education. No matter where they are from or what their background is,” said Yvonne Stennett, executive director at Community League of the Heights (CLOTH).

Stennett started working CLOTH over 40 years ago as a youth advisory counselor and today leads the organization based in Washington Heights, while managing remote learning and a food pantry operation helping thousands weekly.

Stennett is also the founder of the Community Health Academy of the Heights where students participate in remote learning and tutoring during the lockdown. Currently, they have 753 primarily Latinx students, and 100 elementary students, from Brooklyn, Washington Heights, and the Bronx.

She admits her school was a little ahead of the curve in terms of giving out laptops quickly. There is, however, still a small percentage of students that have not gotten equipment. One reason for this is that some students have had deaths from COVID-19 in their families that have turned their home life upside down, said Stennett.

The academy has created a support and wellness team for students including a caseworker, guidance counselor, and two teachers to check in with students daily. The school also pivots to assist parents that ask for help when they don’t understand the material, or if there’s a language barrier.

“I think they’re getting information much differently, and their ability to question and ask for help, that is still missing. The ability to have interaction and enrichment, it’s not happening,” said Stennett about the flaws of remote learning. “It’s like read it, be ready for it, come tomorrow, get online, be ready for a quiz but there’s no supplemental help.”

The main thing she hears often is that kids want to go back to class, and they miss fellowship with other students.

Stennett said remote learning can not exist by itself, it needs support and one-on-one learning or else it will leave major gaps. She believes that her students have so much to overcome already that having a lighter pass/fail system during the pandemic wouldn’t help them succeed in the long run.

City Councilmember Mark Treyger (D-Brooklyn), chair of the Council’s Education Committee, and who taught social studies in public schools for eight years, spoke about its inherent inequities and how students are suffering. He said our schools now more than ever need teachers, cafeteria workers, social workers, sanitation, counselors, and nurses.

“It’s hard to imagine or reimagine anything when New York schools have never been fully funded in the history of New York state,” said Treyger.

For some school communities that were properly funded, having tablets to access at home and the internet is not new, he said. In other places, usually low-income, adjustments to remote learning were stark and some kids are still getting tablets. Treyger said that many of these students are living in crowded dwellings or are essential workers struggling to keep up.

He completely disagrees with the governor’s advisory council or any budgetary cuts.

“It really is quite something to have those in power who have starved the school system for decades, complain about kinds of malnutrition in that very system,” said Treyger. “It was really disconnected from the reality on the ground in many of our school communities. No school community is asking for the advice of Bill Gates, quarantining in a mansion in Washington, when many of our children are in shelters or only received a tablet for the first time within the past two weeks.”

As for grading, Treyger said there’s no way to rank kids in a pandemic but he considers grades up until mid-March crucial. From that crucial point until June, it would be unfair to penalize a student for falling behind.

He thinks the city is at a crossroads, and a decision this big and impactful for generations to come requires collaboration with all school districts and creative thinking on the part of the DOE.

“Technology can supplement instruction, but it can never replace instruction. You can use it as a tool, but nothing can replace a teacher facilitating a conversation in a class and engaging students in meaningful ways,” said Treyger about the future of remote learning.