Pops takes off in the morning to get supplemental breakfast and lunches they handout in the schools. Last year when I went to visit him on Long Island, he smiled wide and invited me to his favorite restaurant at the church’s soup kitchen.

Free food’s a powerful thing. They give him a clear-white plastic bag, the kind that appears weightless when you wrap it around a gift basket. Inside, individually wrapped in the same plastic, are little milk boxes, applesauce, cheese sandwiches, oranges, juice and some form of chickpeas or veggies.

The thing is we’ve always been broke misers on the verge of being in the poor house if we missed a paycheck. I believe food insecure, the working class is the polite term.

It’s hard to imagine that so many haven’t lived that life and are just getting a taste now in the middle of a world health crisis. I think, on some level, it filled me with a deep sense of inadequacy when I was younger but I didn’t know why.

The pain of wading through the medicare system to wait on hold for endless hours, or how humiliating it was to have food stamps or welfare sometimes. When I was little I couldn’t put my finger on it, but as I went to visit the Last Black Man to own property in Williamsburg that runs the local jazz center, aptly called the Williamsburg Music Center, the differences in the way even the virus has affected us is starkly apparent.

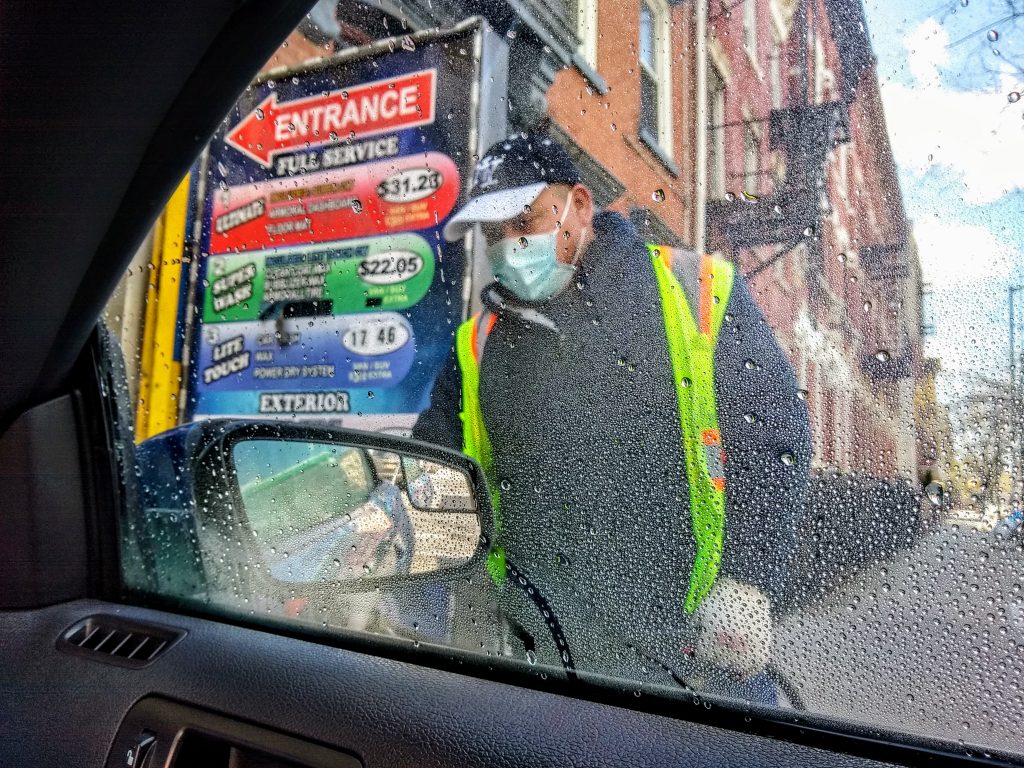

Not that he’s rich at all. He just knows for a fact where his food will come from. It is only really a minor inconvenience that he can’t get seafood or fresh meat from the Whole Foods down Bedford Avenue. A day trip to the car wash for his Mustang is just as important as a supply run. I’m still baffled that the car wash is somehow essential enough to be open.

The center is as shuttered as anywhere else, dust beginning to settle onto the floor and house instruments. As soon as I hop out of the Uber, sent to get me from the other side of the tracks, I pick up a broom and a rag and get to work at my second job. Cleaning.

It’s the middle of the morning, but it’s darker inside, almost ghostly in a century’s old building that’s usually brimming with music and people. I can’t play an instrument, but I can appreciate the all-American handmade wooden frame of a baby grand piano as I wipe it down.

In an abstract way, I know there are rich and famous people all over the city, but to me they lived in beams of sunlight that would sting your eyes if you look directly into them. They live in neighborhoods with no trash on the ground, wealth behind every wall, and a nice sprinkling of celebrity money to give it some clout.

They’re trapped in luxury condos in places like a millionaire and billionaire row along Central Park to the family palaces that line Ocean Avenue and Ditmas Park. Williamsburg isn’t rich and famous. Williamsburg is free-loving and arts and restaurants. Williamsburg is pushed out Puertoricans and Italians.

Williamsburg is living on high, above-average means, but just high enough to have an Apple store and a Starbucks invest in a location next door to your laundromat.

I know people may be dying here too, but it feels emptier and calmer.

“Nah, man they’re all gone. They left. Probably as soon’s this thing hit,” he says, as I finish wiping down the bar and couches. “I’m still here though,” he says, looking at the high ceilings and guitars on the walls that he owns.

He picks up the mop, jazz hands content to clean.

Editor’s note: Williamsburg Music Center is a black-owned Jazz venue that was opened in 1981 by legendary composer, conductor & musician Gerry Eastman. Gerry has worked with artists like Sarah Vaughan, Count Basie, Etta Jones and the Isley Brothers to name a few. To learn more or donate to the space click here.