The Democratic presidential debate held in Las Vegas last night tried to welcome a little more competition.

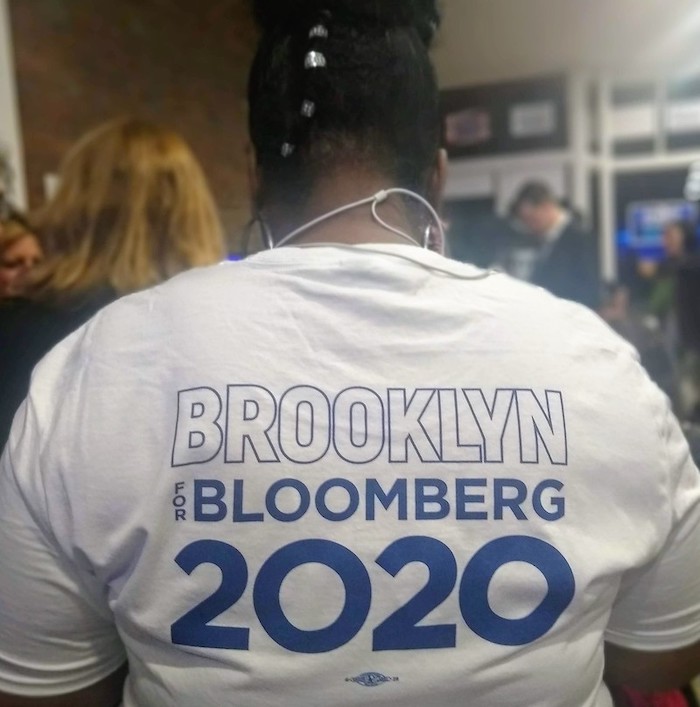

Billionaire Michael Bloomberg made his first appearance on the stage, while fans of the former mayor of New York, gathered around the projector screen in the back of Cloe’s Corner.

Cloe’s Corner is a communal coworking space on 3rd and Atlantic Avenue in Boerum Hill. The facilitator, Cloe Luv, runs a nonprofit called Women With Voices; which supports all women from all walks of life. The building, built in 1915, served as Bloomberg’s headquarters and its debate watch party for the night.

“I support Bloomberg and all he does for minorities,” said Luv. “I’m born and raised in Brooklyn. While he was mayor, I opened my recording studio, my neighborhood was safer. I feel like I flourished.”

The exposed brick walls were bathed in the blue hue of the dimmed lights. A huge, delicious spread of halal foods and falafel, provided by Halal International across the street, was laid across four tables. Most of the people in attendance were Bloomberg supporters. And if they weren’t, then they were fans of at least one of the other five candidates.

They enthusiastically chanted ‘I like Mike,’ and occasionally punctuated the night with bouts of cheers.

Bloomberg has been under fire about some of his mayoral practices. It was to no one’s surprise that moderators and candidates immediately laid into the newbie.

“I feel like opinions like that come from outside people looking in, or someone who was personally affected like their kids went to jail. It’s unfortunate that he followed the data,” said Luv in defense of Bloomberg’s controversial practices.

Luv mentions Bloomberg’s Greenwood Initiative that’s designed to support black homeownership, communities, and businesses. “He’s mending the roots,” said Luv.

Stop and Frisk under the Bloomberg administration, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union, has stopped millions of people since 2002. Black and Latinx communities were overwhelmingly targeted. The procedure continued under Mayor Bill de Blasio, albeit reported stops did sharply decrease in recent years.

“He’s [Bloomberg] not saying it right,” said Nelson C. Dones, a former NYPD officer who lives in Williamsburg. He worked for the city for several decades under different mayors.

“The quotas were what happened in the 90s,” continued Dones. He explains how stop and frisk became systematic even before Bloomberg. “One guy starts counting and another precinct starts counting, and you know they talk to each other trying to figure out why it’s different. Then, it’s required in different precincts. The activity increases. It was all about the number. People became numbers.”

Numbers created a distance that failed to capture the image of walls lined with black men and teenagers with their hands up high and legs spread that became pretty routine in parts of the city.

Policing policies weren’t the only hot topic. Part of the debate labored on redlining.

According to the Brooklyn Historical Society, it’s the systematically racist practice of denying bank loans and property to people of color after WWII. It was a status quo practice, extending to non-whites and immigrants over the decades, that funneled people into segregated neighborhoods. Redlining in America has extremely deep historical roots that are not new, nor even remotely unique to New York City.

Daniel Zaho, 53, is a real estate agent that lives in Flatbush. A Republican turned Democrat, he notes that “this is the first time I’ve ever felt compelled to participate in politics.” As someone in real estate when the topic of redlining was broached, he said that he could understand why banks wouldn’t want to risk lending to people that didn’t qualify financially.

Understandably today, because redlining is illegal on paper. In the past even middle-class or affluent people of color weren’t allowed to live where they could afford to. The housing crisis in 2008, when Bloomberg first made his comments about redlining, was in part due to predatory loans given to people who couldn’t afford to pay back the banks.

As the debates came to a close, there was an overall consensus that Bloomberg could’ve done a little better, performance-wise.

“He’s more of a doer, not a talker,” said a staff member.

“Not a great orator, but after the first break he got comfortable,” said Dones.