A new book published by Cambridge University Press details the crack years in America’s largest cities, including the effects on New York, and their lower-income, generally African American populations that were most impacted by the era.

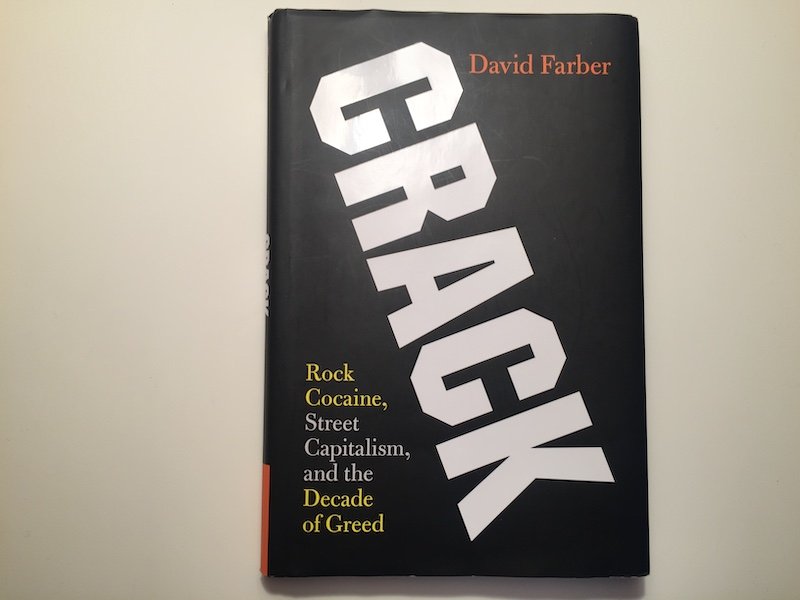

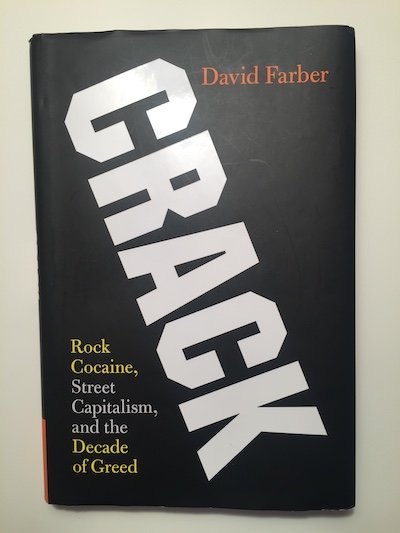

“Crack: Rock Cocaine, Street Capitalism, and the Decade of Greed,” written by David Farber, is a history of the way crack cocaine decimated poor, often minority, communities of the United States, from crack’s cocaine-roots all the way to the political response to the drug.

Crack — made from combining cocaine and baking powder, cooked into small “rocks” — came about after cocaine had already existed in the marketplace for many years. As cocaine went from being socially acceptable for both medical and recreational uses to being considered bad, dealers began to sell it.

It was mainly a drug for upper-class whites, but people of lower socioeconomic status and racial minorities used it as well, to some extent.

It was mainly a drug for upper-class whites, but people of lower socioeconomic status and racial minorities used it as well, to some extent.

By around the 1970’s, crack was beginning to pop up and it spread, both location-wise and in popularity, from then across the country. The mid 1980’s through the mid 1990’s is now considered the crack years.

The book — only six chapters plus an introduction — looks at the crack years for the nation as a whole, but does focus, at some points, on the effects of crack in New York City communities, such as Manhattan’s Harlem and Southland in Queens.

In Brooklyn, as Farber tells it, the crack scene was dominated by rival Jamaican crews, including a posse run by Delroy “Uzi” Edwards and the Gulleymen.

These groups, known to be very violent and prone to murder, had connections to Philadelphia, Dallas and Washington, D.C. Another group, called the A-Team, were found in East New York.

Other than the brief mention of these crack-selling groups, the book didn’t discuss Brooklyn very much, focusing rather on Queens, where it seems a lot of the heavy crack dealing, and usage, occurred.

Crack cocaine hit inner-city, low-income, minority communities hard during the 80’s and 90’s.

Farber explained why these were the places crack did the most damage: “users who believed they had to smoke crack to find pleasure and release from their dire circumstances and the hardened distributors who saw in the destruction of their neighbors and their community the quickest route to their own desires.”

The communities where crack took the deepest toll were poor and often black neighborhoods. During this time period, cities turned from an industrial economy to a service economy; manufacturing jobs that people of color once enjoyed were fast disappearing.

People were losing their jobs and couldn’t find their niche in the service-based job market. Some of the people who were unhappy turned to taking drugs to escape from their situation; other people who were unhappy turned to selling drugs to make the money they wanted to improve their situations.

Besides the complex causes for the crack “epidemic” that affected these certain communities, Farber also effectively communicated the impacts and implications of the era.

While the book’s long sentences did make it a dense and very involved read, it still is able to capture the reader’s attention and provides them with a clear understanding of the situation. Stories of kingpins and gangsters and street dealers infuse the informative text with some narrative color.

Well-placed quotes from people caught up in the crack scene bring heart to the reading, especially those of short-term dealer Corey Pegues, who went on to become a New York City Police Department Deputy Inspector, where he was the commanding officer of the 67th Precinct in East Flatbush among other assignments.

One such Pegues passage was in explaining the reasons for getting into dealing: “You’re young, you’re black, you don’t see any prospects. Then you see these dealers, and they’re living the American Dream … It was impossible to hang around people selling drugs and making money and not get caught up in it.”

“Crack” will give readers, especially white readers, a new perspective on what went on during the crack years and how it was handled. For younger readers who didn’t experience the time period firsthand, it piques interest in something that their parents lived through and have opinions on.

The book’s author, a historian and professor, lived in Manhattan during the height of the crack years with his wife and child, and then later lived near a crack dealing spot in Philadelphia, where he became acquaintances with the dealer, influencing his decision to research and write on this subject.