Months later, the repercussions of a Trump Administration proposed rule change attempting to restrict immigrants from receiving a green card if they have utilized public assistance continue to affect individuals throughout New York City, specifically in the Caribbean community in East Flatbush.

Under the proposed rule change, which the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) released last September, there would be a change in the “public charge rule,” a policy designed to reduce the number of people who are eligible for green cards and other visas.

Congress long ago established that the U.S. government can deny a green card to anyone who “is likely at any time to become a public charge” but without defining what “public charge” means.

Since 1999, immigration officers have adopted the guiding principle that a public charge is someone “primarily dependent on the government for subsistence,” as demonstrated by either (a) using public cash assistance for income maintenance or (b) institutionalization for long-term care at government expense, according to initial reports.

The new proposal would more strictly enforce existing rules for millions of immigrants applying for green cards or visas by scrutinizing their use of food stamps, welfare, housing vouchers or Medicaid.

This has left some individuals in the immigrant-heavy neighborhood of East Flatbush scared to go about their daily lives.

“He has created a lot of fear in the immigrant community and he continues to do so and I’ve heard reports of people who are afraid to go to schools, to pick their children up from school, to go to church, to go out shopping and to bring lawsuits when they may be entitled to do so,” said Roland Ottley, an immigration attorney originally from St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

It would target immigrants who need access to food stamps, medical care and housing assistance, according to immigration attorney Shellon Washington.

“This proposed rule would affect working-class immigrants, especially from the Caribbean, very negatively,” said Washington, who works in East Flatbush. “It will disqualify them from becoming an American citizen.”

The rule will take effect after the Trump administration reads through more than 150,000 comments on the document. After the Administration reads through them, they will write and publish responses to the comments, according to the National Immigration Law Center.

Another factor playing into the issue of deportation is the amount of policing and ICE presence predominant in areas like East Flatbush.

“There’s a way higher police presence in East Flatbush than in a lot of other parts of Brooklyn. It feels like a garrison,” said Albert St. Jean, the New York City organizer for the Black Alliance for Just Immigration. “Black immigrant neighborhoods are overpoliced and the majority of black people who get deported are deported because of over-policing.”

According to the “State of Black Immigrants” report from the Black Alliance for Just Immigration, 16 percent of immigrants from the Caribbean are undocumented and the number of undocumented African and Caribbean immigrants rose from 389,000 to 602,000 individuals from 2000 to 2013.

Undocumented immigrants have never been eligible to utilize public federal benefits in the U.S., according to the Migration Policy Institute. Immigrants waiting to have their cases heard are also at risk.

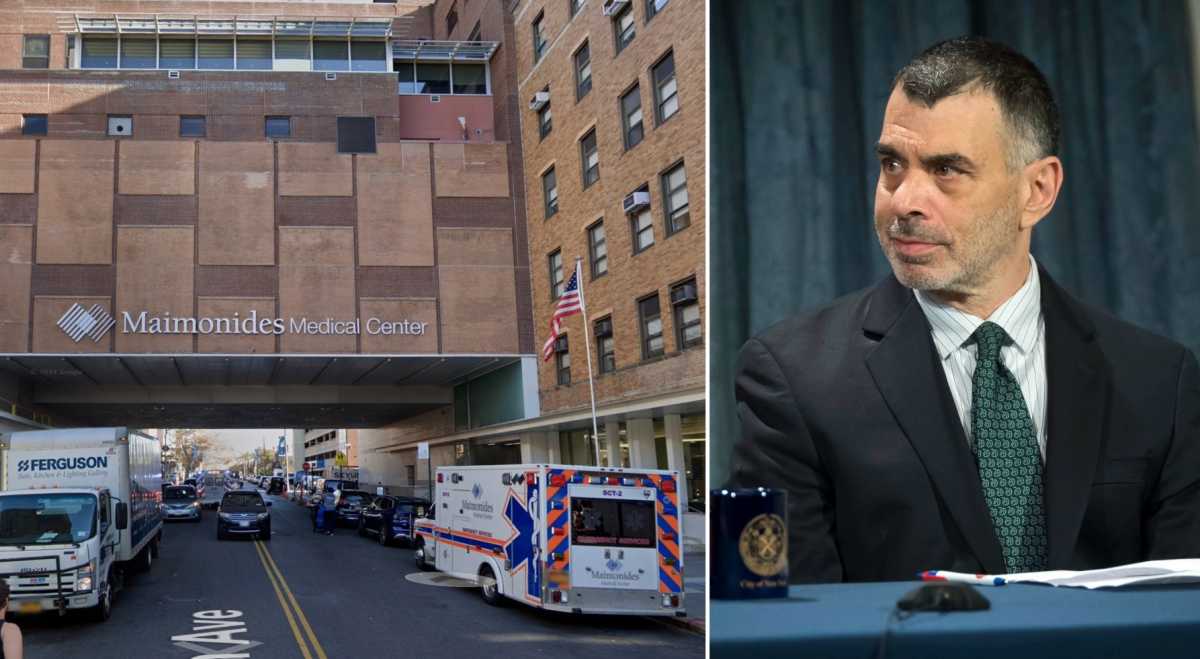

However, Mayor Bill de Blasio, in collaboration with East Flatbush City Council Member Jumaane Williams and Flatbush Assembly Member Rodneyse Bichotte, announced a comprehensive new health plan that will help guarantee health care to undocumented Caribbean immigrants in January 2019.

While there have been no reports of any immigrants dying because of deportation, other effects, such as health issues, could be a problem if they were to return to their native countries, opponents of the new rule warn.

“If someone who has been put on antiviral medication against HIV were to be deported back to Haiti, they would not receive the care that they are receiving here and that can be a really bad situation for their health,” said Andre K. Peck, Executive Director of the Haitian-American Community Coalition. “When people come and ask us questions, we don’t really know what to say because it’s so uncertain.”