Despite New York City’s reputation as a bastion of ethnic diversity, it is still far from perfect. City Councilmember Justin Brannan (D-Bay Ridge, Bensonhurst, Dyker Heights, Bath Beach) sought to help change that when he introduced legislation Tuesday mandating Arabic language translation services at all city polling places that need them.

If the bill passes, all polling places in the five boroughs that represent at least fifty Arabic speakers will be mandated to offer translation services.

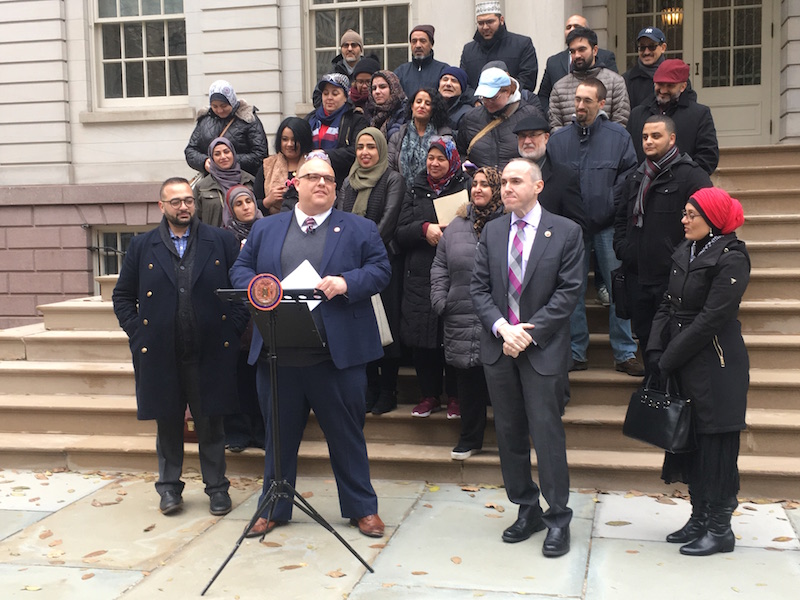

At a press conference about the legislation on the steps of City Hall, Brannan insisted that the bill was crucial to combatting voter suppression efforts, particularly those that target non-English speakers. “Career politicians fear change. Voter suppression slows change down,” he said.

Brannan also beamed about his support for this bill as the representative of a heavily Arab district. “I promised to fight for this,” he said.

City Councilmember Mark Treyger (D-Bath Beach, Bensonhurst, Coney Island, Gravesend, Sea Gate), a cosponsor of the bill, explained why he championed it. On Election Day he was called to a polling place due to his unique status as the first Russian speaker on the city council.

A Russian woman had difficulty determining whether she was in the right place. When a Russian-speaking Holocaust survivor offered to assist her, polling authorities attempted to have them arrested for speaking an unauthorized language in the polling place, Treyger recalled.

Treyger explained that this was wrong, indicating that other languages such as Spanish and Chinese were not stigmatized at the city’s polling places to the same degree. “We actually worked with the mayor and administration for a pilot program for Russian and Haitian Creole speakers,” he said.

Widad Hassan, a community organizer with Yalla Brooklyn, an organization dedicated to advocating for electoral and civil rights for the borough’s Arab and Muslim community, told this reporter of some of the challenges Arabic speakers face when they vote. “There’s a lot of difficulty. Many can’t read English, so there’s lots of anxiety,” she explained. “They often rely on other community members to inform them how to vote.”

Samiyya Rumein, another attendee, pointed out that the reliance of many others in the Arab community on other community members. “Translation at the polling place is a civil right. If they don’t have access to translation services, they can’t really vote fairly,” Rumein said. “Those with political agendas can manipulate them.”

Dr. Debbie Almontaser, Secretary of the Yemeni American Merchants Association, agreed. “Our communities count. Their votes count. Their voices count. I was outraged on Election Day when so many were turned away because they could not read the ballot,” said Almontaser. “It’s outrageous and not acceptable.”

Still, Dr. Ahmad Jaber, Co-founder and Board President of the Arab American Association of New York, indicated that Arabic translation services at polling places isn’t the end of fully enfranchising Arabs in New York and across the nation, pointing out that Arab identity is not listed in the census. “The size of our community is underestimated,” he said.