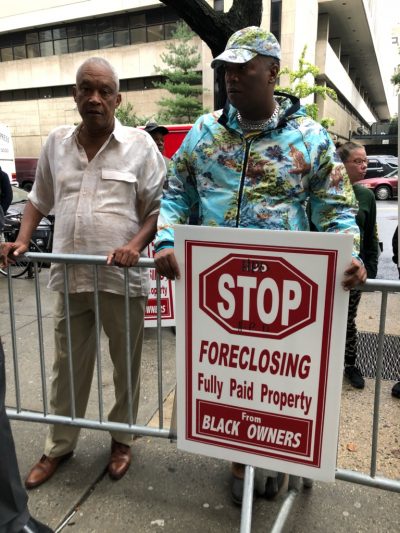

Editor’s Note: The following is the fourth of a KCP investigative series by reporters Kelly Mena and Stephen Witt on how New York City is taking paid off properties from longtime small property owners, including black and brown seniors, and giving them to connected non-profit and for-profit developers as gentrification continues to sweep across Brooklyn.

Last June, McConnell Dorce, 69, felt in his bones that something was fishy after he went to the New York City Department of Finance (DOF) to pay property taxes on the four-unit home he thought he owned free and clear at 373 Rockaway Parkway – a property he bought in 1975 for $25,000.

Going in person to the DOF to pay his property taxes is a ritual that Dorce has done every year for the past 40-some years, and it includes his waiting for confirmation that the payment was processed.

But on this day, DOF officials told him that something was off with their records and that they couldn’t accept payment from him, and that he should go to the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) to get everything sorted out. Once at HPD, Dorce was unable to get a clear response from a single official. Then in a HPD letter dated July 3, the agency requested that Dorce produce ID, his deed, and proof of funds to clear up any violations and to bring his property registration with the city current, all of which he subsequently did in the coming weeks.

Dorce said he went to HPD daily throughout the month waiting for what he was told was a record discrepancy until he received a letter from DOF for “delinquent tax arrears.” The letter also included a list of building violations placed upon his Rockaway property and ways to correct the violations in the sum of about $38,000.

This letter triggered Dorce to personally visit both the offices of HPD and DOF, and was told from both agencies that if he wanted help in correcting the problem he needed to “wait for a call.” This time Dorce wasted no time and traveled to his bank, Citibank, to get written confirmation to present to HPD that he had the funds available in order to pay off a host of violations in which he never even knew about. The bank on Aug. 1, 2018 was able to confirm that Dorce had $43,000 to pay off his $38,000 in arrears that the DOF said was pending on his property tax bill to the City. The letter was presented to the city in person.

Just eight days later, on August 9 of this year, Dorce received a call from HPD asking him to pay for the registration of his building in the amount of $78. Dorce went along with the demand and paid the bill the same day according to his records. But he was still blocked, he says, from paying his property taxes as the DOF said they couldn’t accept payment from him without instructions or clearance from HPD.

By August 13, Dorce was back again where he started, on the other end of a bill that claimed his building was once again in violation of local law and needed to be up-to-code. Dorce then was told by HPD that his 4-unit, family residential property had been charged for housing emergency violations in the form of $8,306.73. The notice left Dorce once again at the mercy of the city’s housing agency who again didn’t detail the violations and gave Dorce the run-around when he inquired about paying off the balance and getting a detailed document on how to repair his building.

By the end of August, Dorce was now being contacted by HPD official Kim Darga, who in a letter to the father of four, stated that HPD had finally reviewed his inquiry involving his inability to pay property taxes and that they “disapproved his request to pay property taxes due to lack of access to his entire building.” Perplexed, Dorce now traveled to the city’s Department of Buildings (DOB) inquiring about the claimed violations that was preventing him from paying his current taxes, of which he had no knowledge.

The city’s August 31 letter was the culmination of months of work by Dorce, an elderly man, who, along with his wife, has worked his entire life for his property, just to find out he still can not pay off his real property taxes, and that the City was demanding he correct violations of which none of the city employees he spoke to could give him a clear account of what they were.

The irony is that unbeknownst to Dorce throughout this entire process is that he no longer owned the property. That’s because the city took his property, along with more than 60 others and bundled them together in a single court proceding that was filed in July 2017.

Court documents show that the properties were identified by block and lot numbers with no owners named, meaning none of the property owners were ever legally served, giving them no ability to have their day in court to defend themselves.

Despite this, Kings County Supreme Court Judge Mark Partnow on Dec. 14, 2017, just two weeks before Christmas, entered a judgement to foreclose on all the properties.

These properties wwere then placed in HPD’s Third Party Transfer program, in which Neighborhood Restore, a non-profit third-party working with the city had been given the property. They in turn handed over the properties to non-profits and/or for profits for managemnet/ownership rights.

But Dorce, not knowing any of this at the time, dutifully requested a run off from DOB of the violations logged against the property, which he received in a multi-page report in September. With this revelation, Dorce says he immediately, traveled to DOB and invited DOB to visit the building to inspect it, and to inform him in person about any corrections they wanted done.

DOB did arrive to the property nearly a year after the foreclosure judgement with the inspector telling Dorce everything was “perfect,” but that he had to return with his supervisors.

Dorce accounts that what followed was an odd and curious inspection of everything from the nails in the wall to the new boiler he had recently installed to the fresh paint job he had applied in the building this past summer. Dorce was told by the group of inspectors that he didn’t pass and that HPD would be back the next day to inspect his property again. This is when, according to Dorce, five men came to inspect his property and each one of them found a host of violations.

Still, Dorce says, “Not once did a city official tell me I was not the owner of the property. I maintain that I was the deed holder. No one even mentioned that I was divested of ownership to the building and I feel tricked. No one disclosed information when I pressed them for details and not once gave me the impression I was not the owner of the property.”

Dorce said he finally learned he no longer owned the property after MHANY fliered the building to notify the four-tenant families living there of a Sept. 17 meeting regarding new management, new building policies and redevelopment possibilities.

It was around this time, less than two weeks ago, that one of the tenants gave Dorce a notice sent to her apartment from Neighborhood Restore, the City’s affiliate, that they and not Dorce, now own and control the property.