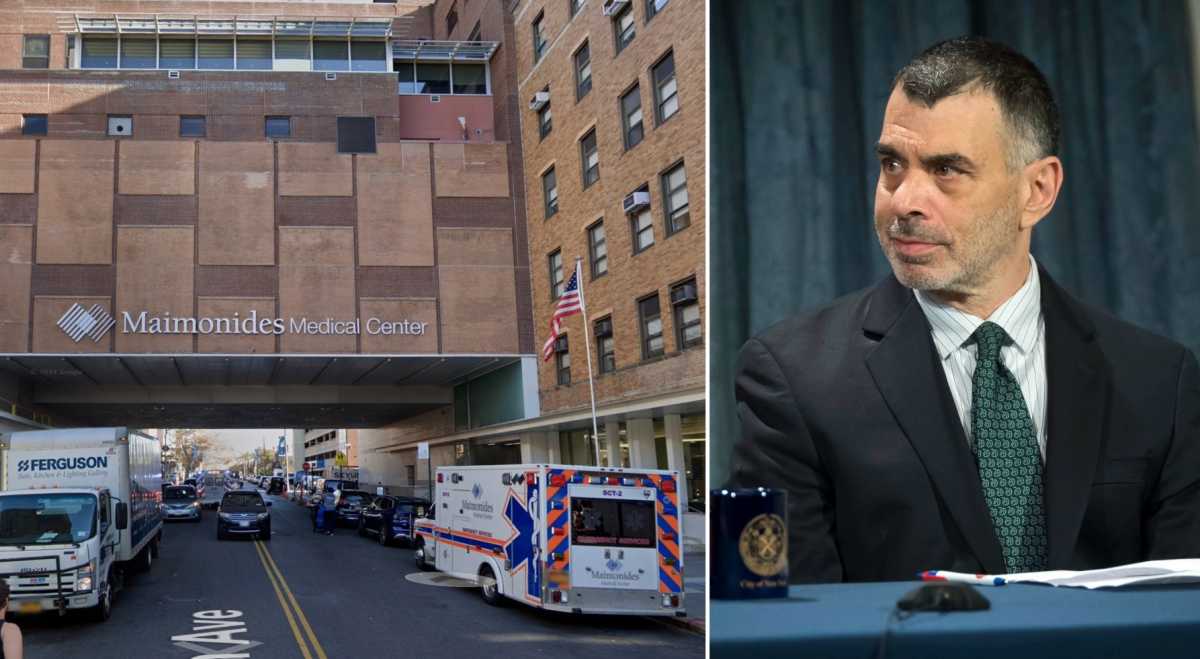

City Councilman David G. Greenfield (D-Borough Park, Bensonhurst, Midwood) a Georgetown Law School graduate, attorney and adjunct law professor, saw one of his pieces of legislation help the U.S. Supreme Court decide a landmark religious liberty case recently.

The measure cited was Greenfield’s 2016 school safety law, which provides $20 million in public funding for security guards to yeshivas and other non-public schools.

In Trinity Lutheran v. Comer, a church’s pre-school applied to the State of Missouri for a grant to reimburse the cost of resurfacing its playground with rubber from recycled tires. The state denied the grant, citing a so-called Blaine amendment to its constitution that “no money shall ever be taken from the public treasury, directly or indirectly, in aid of any church, sect, or denomination of religion.”

Trinity Lutheran took Missouri to court, arguing that it violated the U.S. Constitution’s Free Exercise Clause by forbidding religious institutions from competing with secular organizations for public funds.

During oral arguments, Justice Samuel Alito asked attorneys whether Greenfield’s New York City law would be acceptable under the Missouri constitution and whether public money could be used on security infrastructure for at-risk religious institutions.

James Layton, the attorney representing Missouri, maintained that Greenfield’s law would not be acceptable under his state constitution, an answer that Alito found unbelievable.

“This is a New York City program that provides money for security enhancements at schools where there’s fear of shooting or other school violence,” Justice Alito reiterated.

Alito was one of the seven Justices on the court to rule in favor of Trinity Lutheran. The majority included two of the Court’s three Jewish justices, Justice Stephen G. Breyer and Justice Elena Kagan.

“The First Amendment says that the government may not prohibit the free exercise of religion, and that means that government may not discriminate against religious institutions that would otherwise be eligible for government funding,” Greenfield said.

In his majority decision, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. called it “odious” to exclude a religious institution from a public benefit and said that Missouri expressly required Trinity Lutheran “to renounce its religious character in order to participate in an otherwise generally available public benefit program,” making its inability to compete for the grant express discrimination against religious exercise.

The Justices were alerted to Greenfield’s law by the Orthodox Union, which submitted a “friend of the court” legal brief to impress upon the Justices how their decision could affect lives far outside Missouri, including the lives of yeshiva students in New York.

Ultimately, the Court’s decision appears to bode well for advocates of yeshivas and other religious schools across the country.

“As an elected official, I feel validated that the Supreme Court has taken a stand against religious discrimination,” Greenfield said. “Government has long provided operating funds to benefit schoolchildren at religious and secular schools alike from textbooks to nursing to security guards. As a result of this decision, schools that educate religious children will now be able look to government for other funding as well.”