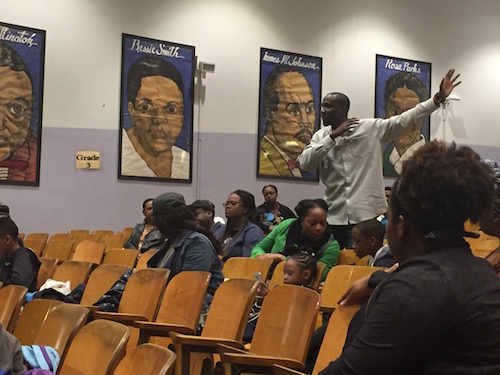

Parents of elementary school students last night demanded clarity, transparency and open lines of communication from city officials following the recent discovery of elevated lead levels in the drinking water at PS 289 George V. Brower School, 900 St. Marks Avenue in Crown Heights.

Representatives from the Department of Education (DOE) and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) came to the school to educate and answer questions from concerned parents who were recently informed of high lead levels at the school. The high lead levels were first reported by the New York Post.

“It was frightening waking up after spring break to see the news,” said Parent Ruqquyah Demesvar.

DOE confirmed their findings of lead levels as high as 1000 times the allowable threshold but concluded that the levels were an isolated issue probably resulting in stagnant water or underused fixtures.

“We drew 160 samples and 29 of them had elevations. If there was a systemic problem in this building, all of your samples would have come back with elevation,” said Aloysee Heredia Jarmoszuk, chief of staff for Deputy Chancellor Elizabeth Rose. “We know the issue is specific to fixtures in the building.”

Jarmoszuk informed parents that every source of water used for drinking and to prepare food was tested on December 15, 2016, wherein which the results of elevated lead levels were supposedly “backpacked” to all students. However, no parents attending the meeting claimed to have received notification of any lead issues prior to reading the Post story.

“It’s the steps that the school did not take that put us in a place where we’re concerned and we’re stressing our kids,” said an attendee.

Once abnormally high lead levels were detected, DOE made the necessary repairs to two water fountains within a month’s time. Jarmoszuk told the attendees that notification of the initial testing, subsequent repairs, water fountains closures, future testing results and procedural efforts meant to maintain healthy water levels were all sent to parents.

However, parents maintained that of the five letters DOE claims to have sent, only one letter dated April 19, 2017 has been received – two days after New York Post’s article.

“When we’re talking about kids, when we’re talking about lead, whether it’s high or low, it’s still your child, [it’s unfortunate] when you don’t get that communication,” said Sheldon Austin, a concerned parent. “The bigger issue is that no one knew.”

Jarmoszuk told parents that acting interim principal, Marc Mardy will supplement backing packing methods with a text roster and email list-serv to better distribute information to parents. Parents can also refer to the school’s DOE webpage as well as the water safety section on the DOE’s website.

Andrew Fasciano, a representative of the DOHMA offered suggestions on lead testing and remedies that can lower potential lead contamination, such as running water in your home up to one minute before ingesting. A procedure P.S. 289 will have to adhere to every Monday morning for two hours before staff and students enter the building. In an effort to eliminate stagnant water, the school will have to undergo weekly precautionary flush-outs.

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams was also present at the meeting and had a contrasting position to that of the DOE with regards to lead found in the borough’s schools.

“I do not share the same mindset that we don’t have a lead problem in the city. We may not have a public safety crisis right now, but there’s a lead problem if it’s in one pipe, in one school, in one water fountain,” said Adams.

PS 289 was built in 1958 and serves 419 kids in pre-K through fifth grade.

According to another Post story, Brooklyn has by far the highest number of elementary schools with elevated lead levels in their water that registered 20 or more tainted taps — with 18 schools falling in that category.

Currently the state mandates that the DOE tests schools for lead every five years.