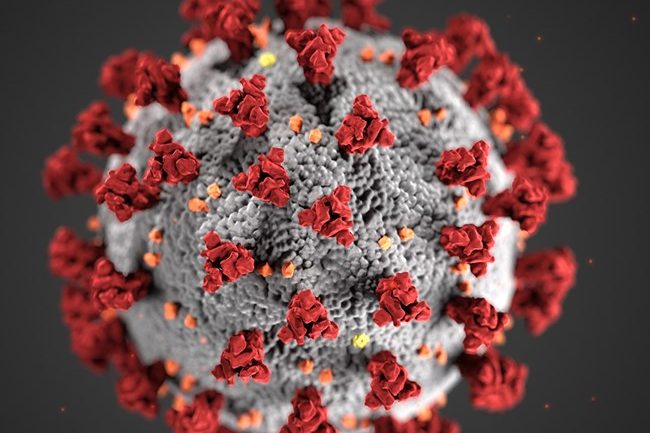

Since March, we have been in the midst of a public health crisis. But the novel coronavirus isn’t the only threat to public health that we’re facing right now; due to widespread lockdowns and disrupted supply chains, millions of New Yorkers are risking starvation and malnourishment.

For this reason, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer (D) moderated a panel discussion last night regarding how to help food insecure New Yorkers during the pandemic.

The discussion took place last night at 6:30 p.m. Brewer accompanied a panel of experts, consisting of food journalist Mark Bittman, NYC Food Czar Kathryn Garcia, World Central Kitchen CEO Nate Mook, GrowNYC President Marcel Van Ooyen, and community leader Maurice Winley.

“This COVID disaster is unlike anything our country has faced before,” said Nate Mook, whose company has provided millions of meals to disaster victims since 2010. “It is not in one specific area; it is not sparing anybody. And I think as time goes on, we have gone from a health crisis to an economic crisis, that we’re now seeing become a humanitarian crisis, as families are unable to put food on the table.”

The panelists identified two groups who are particularly at risk for food insecurity: senior citizens and schoolchildren.

Although COVID-19 can kill anyone, it’s particularly dangerous to patients aged 65 and older. As such, seniors often rely on programs like FreshDirect to deliver their meals, due to the risk they face just by going outside.

But according to Maurice Winley, not all seniors are lucky enough to have access to those services. Winley, who runs the Living Redemption food bank in West Harlem, said that he frequently sees elderly patrons waiting on absurdly long lines for their next meal.

“It’s heartbreaking to see a senior waiting on a line,” said Winley. “Obviously, we expedite service for them. But there are so many seniors who don’t have an advocate, who don’t have someone to accompany them.”

Meanwhile, many of our students rely on their schools to provide them with lunch – and widespread school closures left them going hungry. In mid-March, the City converted 435 public schools into “grab-and-go” meal hubs, where parents can pick up meals for their children.

“We have school locations across the five boroughs, where we’ll serve north of 500 to 50,000 meals [per day],” said Kathryn Garcia.

But the panelists agreed that we shouldn’t just be looking at short-term solutions to the crisis. COVID-19 has exposed glaring flaws in our food economy, and these problems need permanent fixes if we want to be prepared for the next crisis.

One problem is our reliance on external supply chains. According to Garcia, 80 percent of the food consumed east of the Mississippi River is produced on farms west of the River. The disruption of those long supply chains has hindered our ability to feed ourselves.

Going forward, said Nate Mook, we need to think about “staying local” and harnessing the resources we have in-state. As he explained, his company often relies on utilizing local food sources to help impoverished communities.

“We don’t just parachute in from the outside with all of the solutions,” said Mook. “What we do is use our expertise and experience to uplift and leverage what’s already on the ground quickly. In Puerto Rico, for example, why would we be bringing in bread from Miami when we could activate those bakeries in Puerto Rico and get them back up and running? It’s a similar situation with this pandemic.”

But the issues with our food economy go beyond the local stage. As Mark Bittman explained, our food economy incentivizes the production of food that’s both unhealthy and unsustainable. For instance, the federal government spends billions of dollars each year subsidizing corn, much of which goes towards the production of high fructose corn syrup.

Fruits, nuts and green vegetables – which the federal government classifies as “specialty crops” – receive paltry federal support by comparison.

“It’s not just COVID that’s a national problem; it’s agriculture and our food system,” said Bittman. “We incentivize the growth food that’s hurting us and hurting the land. But if we recognize that food is difficult to grow and difficult to get to many, many people, and that it’s just as important as universal health care, as ensuring access to electricity and helping people survive in other ways, then maybe the recognition is that we need to incentivize the production of good food and make it possible to get that good food to as many people as we possibly can.”