I suppose it was too much to expect that Mayor de Blasio’s short-lived presidential campaign would have taught him some lessons about the limits of his brand of politics. Instead, it seems he feels empowered to pick a fight on the issue of civil service personnel file privacy that has him simultaneously battling first responders and corrections officers statewide, fighting with the New York Post, alienating suburban State Senate Democrats, and quarreling with his own police commissioner and Civilian Complaint Review Board.

Here’s a tip for Hizzoner – when you find yourself in a hole, stop digging.

Section 50a of New York’s Civil Rights laws requires a court order to obtain information from the personnel files of first responders. This necessary threshold is in recognition of the unique nature of police work, with law enforcement professionals regularly entering situations defined by uncertainty and immediate risk. It’s appropriate that complaints, for example – both founded and baseless – not be able to be gotten through the same process used to obtain other public agency data or the mayor’s schedule.

Which isn’t to say that this information isn’t routinely provided. It is, all the time. District attorneys, federal agencies, the State Attorney General’s office, inspector generals, civil lawsuits, divorce proceedings – all of these officials and proceedings secure personnel information, but with the privacy protection of a judge weighing the merit of the request and how the information will be used.

The radical left activists now dominating politics have no patience for due process. They want what they want when they want it. Case in point – last week’s State Senate hearing on 50a. One after another, activists testified about how the deliberate personnel privacy process now in place somehow aggrieved them. Whatever their loss and awful sadness, for which the city truly grieves, headlines never make good policy.

The reckless use of social media, ironically criticized by the same activists who want to put cops’ personnel files online, when it harms their causes, makes 50a protections more important than ever.

We’ve learned – thanks to New York Post reporters Craig McCarthy, Bernadette Hogan, Bruce Golding, and Julia Marsh – that de Blasio prevented the Police Department and Civilian Complaint Review Board from appearing at last week’s 50a hearing out of initial fear, we can only surmise, that they would provide opinions other than the lockstep talking points out of City Hall’s “fairest big city in America” playbook.

Doubling down on this dysfunction, the mayor himself then attacked that paper for imbalanced reporting, despite several requests for comment which were all rebuffed.

Police, corrections officers, and other first responders in every part of New York State – Long Island, NYC, Westchester and Rockland counties, the Hudson Valley, Capital Region, North Country, Southern Tier, and Western and Central New York – all deserve better than this circus of finger-pointing and denial on an issue of statewide consequence.

New York is a vast state of diverse regions, with priorities different than those being pursued by the “professional left.” The Democratic State Senators who won in communities outside the five boroughs, whose wins in 2018 gave Democrats one-party control of state government, would be wise to flex some suburban and rural muscles in response to the agenda of their city-based colleagues. It’d be wise for these newly elected senators to keep a “whole state” view of policies impacting law enforcement and keep in mind the city-centric ambitions that lost their brief senate majority back in 2010.

The Sergeants Benevolent Association, the diverse union I have the honor of leading, represents the rank at which policy becomes policing. We are well-positioned to see what works, and what doesn’t. 50a works. Playing politics with law enforcement doesn’t.

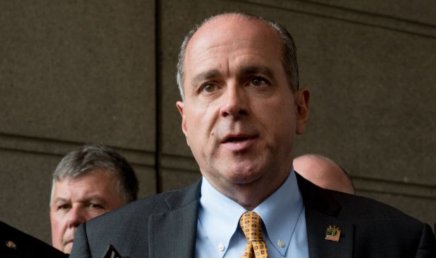

Ed Mullins is President of the Sergeants Benevolent Association of the New York City Police Department.