Kings County Politics city real estate scandal series that has saved millions of dollars of intergenerational wealth in the city’s black and Latino community is getting high-brow artistic treatment in two upcoming exhibitions – including one at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2019 Biennial.

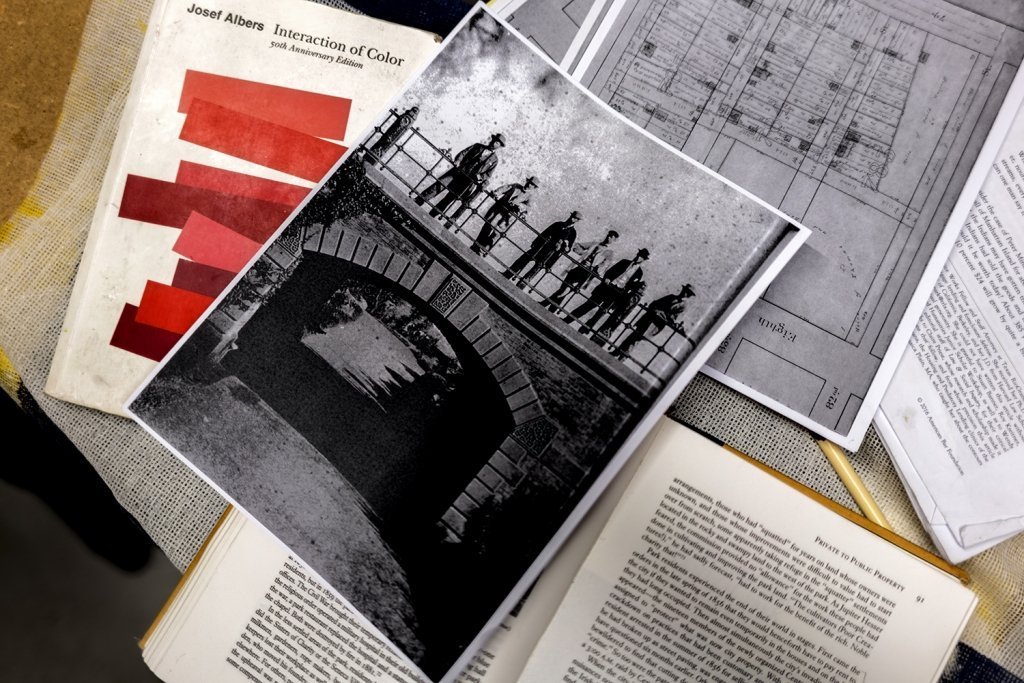

Tomashi Jackson, a Cooper Union Fine Arts undergrad and Yale Master’s of Fine Arts graduate, was inspired to embark on a new body of work and research merging photographic images from KCP’s investigative series with archival materials that explore the hard-to-visualize story of Seneca Village, which was located in what is now present-day Central Park.

“Sometime last year, I came across your journalism. I came across one of the first three pieces in your series of what you guys call the,‘The City Real Estate Scandal,’ about the city’s Third Party Transfer program. I came across the pieces and I immediately thought of Seneca Village, which was a primarily black owned-community of about 800 acres in what is now Central Park,” Jackson told KCP reporters Stephen Witt and Kelly Mena.

Seneca Village was a small settlement of mostly African American landowners in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, at the present site of Central Park. The settlement was founded in 1825 by free black people – the first such community in the city and one of the first in the nation– although it also came to be inhabited by some Irish immigrants.

At the time, land ownership had important political ramifications — African-American men could only vote if they owned at least $250 of property.

However, in 1853, the state legislature approved using eminent domain to seize more than 800 acres of land that would become Central Park. Two years later, around 1,600 people — including more than 250 from Seneca Village — were unceremoniously evicted to make way for the landscaped greenery. Though they were given money for their property, they were still booted from their homes, some violently, according to the New York Times.

“I keep seeing correlations between the dispossession of those people and the attempted this possession of the people in the series,” said Jackson.

At its height, Seneca Village numbered more than 350 people and had three churches, two schools, and two cemeteries. Media at the time, described the population as “squatters and the settlement as “n***er village.”

“I find more and more that I am undeniably implicated in the targeted nature of normalized dehumanization that targets people of color, specifically black people in the United States. Apparently, some people don’t feel empathy for these ongoing horrors that black and brown communities continue to experience,” said Jackson.

Jackson is looking to use color and print to merge the seemingly similar stories-Seneca Village landowners in the mid-1800s getting robbed of their property and TPT Programs seizure of land across black and Latino communities in present-day New York City to show the targeted nature of policy across minority communities.

“My work has a lot to do with color. I employ color and I seek to understand my own compositional issues though abstraction and organization under a historical umbrella or painting and printmaking. I am interested in the history of publication and printmaking. That’s just how the work functions. But I’m also interested in humanism and human rights in general, ” said Jackson.

Jackson is using the groundbreaking historical 1992 text ‘The Park and the People’ by Elizabeth Blackmar and Roy Rosenzweig to delve into the sordid history of black ownership in New York City.

“I can tell that when I start talking about this work, there’s an initial polite listening, maybe even some nodding but it’s not until I pull out my phone and start reading directly from your suite of articles about this scandal and when I pull out The Park and the People by Elizabeth Blackmar and Roy Rosenzweig, and I start reading from the excerpts that I feel collide the most. People’s eyes get wide, they gasp, and then they ask me to repeat things,” said Jackson.

One piece includes a picture of Mr. McConnell Dorce merged and slightly overlapping a portrait of Albro Lyons in two different but slightly similar shades of red. Lyons was a prominent black abolitionist and property owner alongside is wife Mary Lyons in Seneca Village.

“I’ve taken these two photographic images from two seemingly disparate period times but obviously they are not. I’ve broken them down into halftone lines. Lyon is printed in fire red and McConnell Dorce is printed in processed magenta. And here at the center, the lines collide to make a cross-hatch. I feel like this is one of the more clear examples of an attempt to look at a societal problem using achromatic color problem to visualize this colliding history. Because unfortunately, they are so similar is almost hard to perceive the difference,” explained Jackson.

Three of Jackson’s pieces will be featured at the 2019 Whitney Biennial, that also includes work from 75 artists working in painting, sculpture, installation, film and video, photography, performance, and sound. Introduced by the Museum’s founder Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney in 1932, the Biennial is the longest-running exhibition in the country to chart the latest developments in American art.

“Unless the creative process leads to a product that isn’t meant to be seen or shared, the effort is inherently political. Political meaning more than one person, not solitary. Meaning engaging or participating with someone other than myself. I was very influenced by the public artists who really shaped me in my teenage years,” said Jackson.

Jackson will first look to debut the work in 20 pieces at the Tilton Gallery, at East 76th Street, later this month.

“My goal is for these narratives to be felt rather than told outright. I feel like people understand that in my paintings when they are complete,” said Jackson.

For tickets to the 2019 Whitney Biennial, click here. The show will run from May 17 to Sept. 22 at 99 Gansevoort Street in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District.